Sensory setback expands horizons for Fulton Schools PhD engineering grad

Bryan Duarte will put his computer science and haptics skills to use for national defense and to find new ways to aid people with blindness or low vision

Above: Miss Arizona 2018, Isabel Ticlo (right), an Arizona State University alumna, met with computer science doctoral student Bryan Duarte (center) and Academic Associate Abhik Chowdhury in the Center for Cognitive Ubiquitous Computing, or CUbiC, in ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. Duarte and Chowdhury gave Ticlo a demonstration of the center’s haptics technologies. As part of her efforts to support people with vision disabilities, Ticlo was interested in Duarte’s project to enhance situational awareness to enable nonvisual travel for those who are blind or have low vision. Photographer: Ding Ding Zheng/ASU

(All photos in this article are archival images taken before the current pandemic social distancing and face covering requirements went into effect.)

Soon after Bryan Duarte completes work for a doctoral degree in computer science, he will start working for the U.S. Department of Defense. That’s all he is authorized to say about what he will be doing on the job.

If Duarte’s role requires expertise in a wide range of technical and strategic endeavors, the broad scope of his education in Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering almost certainly prepared him for endeavors demanding a versatile skill set.

Those learning opportunities were provided not only by the various courses he took but also by the challenges his own perceptual disability presented him in traditional learning environments.

Duarte had intended to enter the job market after earning a bachelor’s degree in software engineering in 2016. But in large part due to his productive efforts to overcome those challenges, Fulton Schools Assistant Professor Troy McDaniel strongly suggested Duarte consider an alternative path: getting a doctoral degree.

McDaniel is the director of the HAPT-X Laboratory and director of the Center for Cognitive Ubiquitous Computing, or CUbiC, where researchers apply human-centered multimedia computing to the development of assistive and rehabilitative technologies for people with disabilities.

McDaniel saw Duarte as perfectly suited for work to advance the field of haptics. Haptics technologies use combinations of force, vibration and motion in feedback loops designed to guide or manipulate movements that enable or augment a user’s physical and sensory capabilities.

Duarte has a keen understanding of the value of those technologies and how they can help people. He became blind as a result of a motorcycle accident in 2004 in his hometown of Casa Grande, Arizona, shortly after he had graduated high school.

Bryan Duarte visited the STEM & Sports Summer Camp at the Ahwatukee Swim and Tennis Center during the camp’s iRobot week. Duarte and Abhik Chowdhury talked to the students about CUbiC’s assistive technologies for individuals with disabilities — and about the importance of inclusion and helping people. Photo courtesy of Ahwatukee Swim and Tennis Center.

By 2007, he had moved to Colorado to live at a residential training center that taught independent living skills. Then, in 2008, he became a stay-at-home father of three children for almost four years.

In 2012, eight years after the accident, Duarte was able to begin his college education at ASU and pursue an aspiration to be an engineer.

Despite his ardent ambitions, Duarte says the nature of his blindness still presented numerous obstacles to accessing complex course materials — particularly the materials needed to learn the advanced math, calculus, design and visual elements essential to engineering. Duarte overcame those challenges and by the time he had completed his undergraduate studies in 2016 he had job offers from major technology companies.

“Getting a PhD wasn’t even on my radar,” he says. “I wrestled with it. I prayed about it. I talked to my pastor about it. I talked to friends about it.”

At the same time, again with McDaniel’s urging, Duarte applied for the Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship, or IGERT, a National Science Foundation program that supports the education of promising doctoral scientists and engineers.

His acceptance into the traineeship provided the incentive he needed to decide he couldn’t pass up the opportunity to help find ways to serve the unmet needs of people who are blind or have low vision.

Duarte’s work to help students overcome accessibility challenges began during his undergraduate years and included starting two clubs for students with disabilities. The goal, he says, was getting disabled students to more fully engage in the social, educational or athletic opportunities the university experience has to offer. The focus was on uniting students with a disability with their peers around common interests to help facilitate community engagement and break down social barriers.

Duarte also did his share to improve his fellow ASU students’ experiences. He was involved for three years in both ASU’s undergraduate student government and its social change community organization, Changemaker Central, and mentored students through the Fulton Schools Career Center.

Those who have worked with Duarte throughout the journey to achieve his educational goals say he has done much to help shape the way services are provided for students at ASU who have disabilities.

“Whenever Bryan had difficulty with access to information in a class or a lab, it was never just about him having a problem,” says Chad Price, director of Education Development and Disability Resources for ASU’s Student Accessibility and Inclusive Learning Services.

“Bryan always wanted us to work with him to find ways to solve those problems for everyone,” Price says, “and for us to bring faculty and staff together to come up with ways to do it for students who for whatever reasons needed better accessibility.”

Duarte’s mission at ASU the past few years “wasn’t just to get a PhD. He is very altruistic. He wants to impact people’s lives,” says Christina Sebring, a Fulton Schools academic advising coordinator who helped to guide Duarte through his doctoral studies.

Duarte didn’t ask that courses better accommodate those with impairments only to make it easier on himself, Sebring adds.

“He’s got a lot of passion about enabling everyone to be included in the experience, and he wants to change how engineering education is conducted so it will do that,” she says.

Allison Curran, an assistant director of academic services, also advised Duarte as he pursued his degrees in the School of Computing, Informatics, and Decision Systems Engineering, one of the six Fulton Schools.

“Bryan knows how to connect with people and to convincingly explain his perspective to them. He takes a very professional approach in his advocacy,” Curran says. “We now have several students who take the initiative in advocating for changes they think are needed, and I think Bryan laid the groundwork for this.”

Duarte doesn’t take all the credit for his accomplishments. In an e-mail he recently sent to ASU President Michael Crow, Duarte gave details about the ups and downs of his college experience and effusively expressed his gratitude for faculty members, advisors and administrators who have “gone above and beyond the call of duty” and “walked through fire with me” to support his academic work, research and advocacy.

Duarte says he was also motivated by CUbiC’s founding director, Professor Sethuraman Panchanathan, who is on leave from ASU while serving as director of the National Science Foundation.

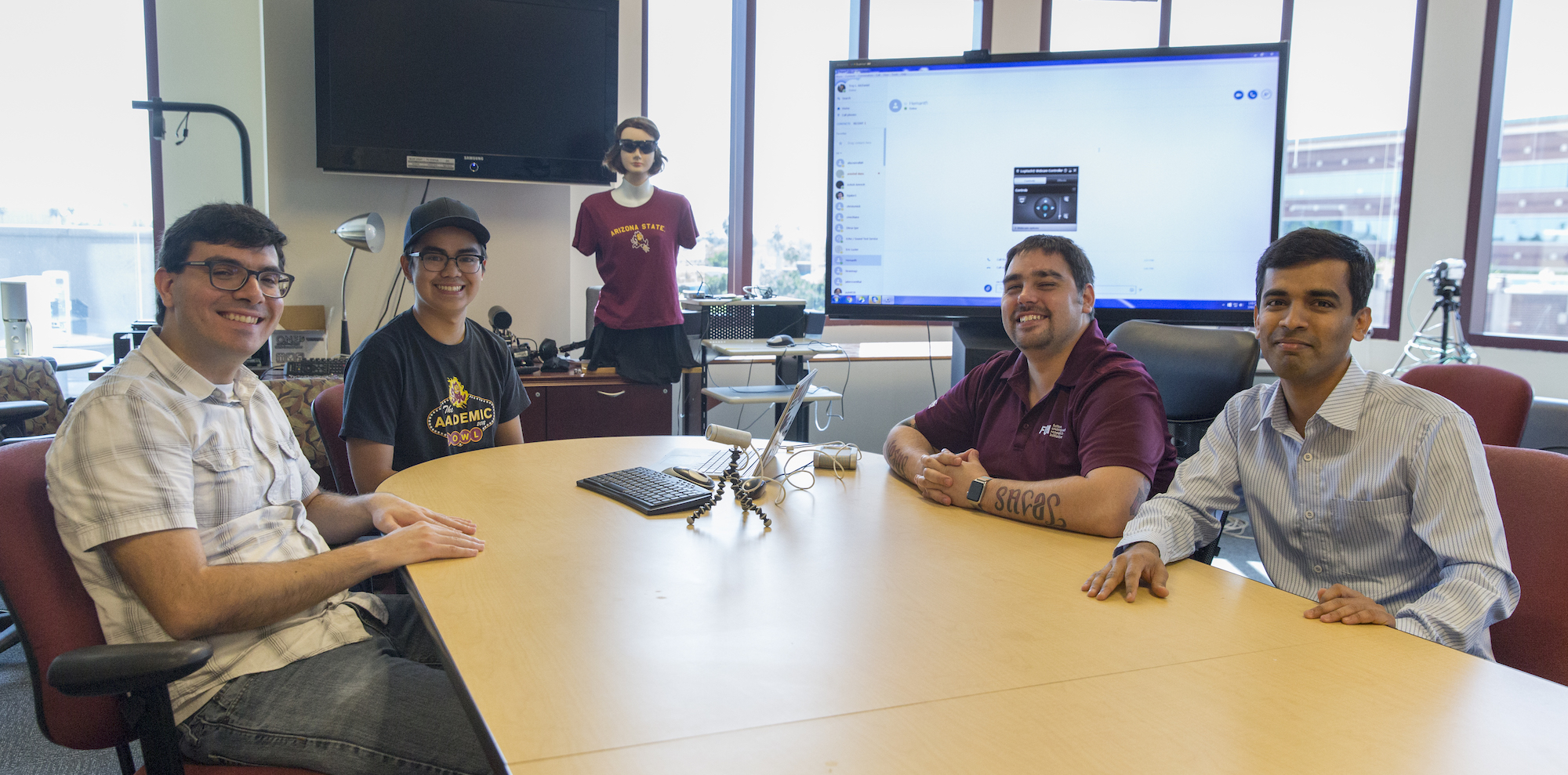

CUbiC researchers meet to prepare a demonstration of their “social interaction assistant” and other assistive and rehabilitative haptics technologies. Pictured from left are Assistant Professor and CUbiC Director Troy McDaniel, former computer science graduate student Jose Eusebi, “social interaction assistant” Suzie (in background), Bryan Duarte and Assistant Research Professor Hemanth Venkateswara. Photographer: Jessica Hochreiter/ASU

Even before Duarte joined CUbiC, he and McDaniel had begun talking about accessibility and how to improve it.

“We would brainstorm for hours about the kinds of devices and technology that need to be developed,” Duarte says. “Later, he told me it was then that he knew I would make a good PhD student.”

McDaniel says Duarte “just had this creative way of thinking about these things in a way no one else did, and he was energized by the ideas we were coming up with.”

Through his doctoral student position in CUbiC and support from the IGERT program Alliance for Person-centered Accessible Technologies, or APAcT, Duarte’s research has spanned across the areas of sensory substitution and augmentation, human-computer interaction, haptics and assistive technologies. His main research focus has been on using haptics to augment the way nonvisual travelers are able to access details of their immediate surroundings through the sense of touch.

Through an internship with Lockheed Martin, he also worked on a project to develop systems to enable pilots to navigate aircraft in critical conditions in which there is zero visibility.

McDaniel says Duarte not only became more technically proficient, but also learned how to develop research projects and manage lab teams, and to communicate about the science and engineering involved in his work to those outside of his field.

Duarte’s enthusiasm for his work was on display when government officials visited CUbiC and he struck up a conversation with a Department of Defense senior director who soon after began prodding Duarte to apply for the government position he now has.

Price, McDaniel and others who have worked with Duarte say the undisclosed nature of the job he will do for the federal government likely indicates that Department of Defense officials see him as sufficiently trustworthy, reliable and skilled to be involved in what are likely crucial aspects of the department’s mission.

At first, Duarte says, he wasn’t interested in a government job and did not want to get involved in anything professionally that he thought could become political.

Now, Duarte sees his role in that job as an opportunity to continue contributing to the well-being of others.

“When I found out about the kinds of things they are doing, I definitely saw ways I could utilize what I’ve learned in school to do some good,” Duarte says. “So, I was like, ‘Yes, I’m in.’ This could be a good career.”