Sensing danger

ASU engineering research seeks to empower electric utilities for more targeted wildfire response

Wildfires are becoming more widespread and destructive. The total area they burn in the United States has expanded by an average of almost 200,000 acres each year for the past three decades. Financially, eight of the 10 most devastating conflagrations in American history happened during just the last five years.

Meanwhile, the global incidence of extreme blazes is projected to increase by 50% before the end of the century, according to a recent report from the United Nations. The agency therefore calls for a radical shift in societal orientation away from reaction and response toward greater prevention and preparedness, including more investment in technical monitoring systems.

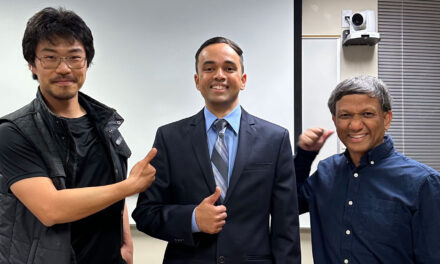

Anamitra Pal, an assistant professor of electrical engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University, is leading new research to develop and deploy such a monitoring system for electric power infrastructure. Power lines and other grid equipment stretch through remote wilderness that is susceptible to wildfires, and relative isolation poses a significant hurdle to understanding and managing risks.

“The relationship between wildfires and the power grid is complex,” Pal says. “Where exactly is a fire relative to power lines in some distant area? How much of a particular line’s capacity is reduced due to that fire? What’s the best time to take a line out of service? Right now, there are fundamental gaps in the sensing capabilities and in the decision-making methods needed to answer these questions.”

Pal and his colleagues are seeking to close those gaps through development of a Wildfire Awareness and Risk Management, or WARM, system. It will configure Internet of Things wireless sensors to monitor the environment around power transmission equipment in isolated settings and apply the data to facilitate resilient grid operation during periods of high wildfire risk.

Their effort is supported by a $1.5 million award from the Addressing Systems Challenges through Engineering Teams, or ASCENT, program at the National Science Foundation. ASCENT encourages collaborations among research communities devoted to devices, circuits, algorithms, systems and networks. It seeks bold, unconventional proposals expected to yield disruptive technologies that address the most pressing societal challenges.

The WARM project team intends to raise real-time situational awareness and develop methods and strategies for more successful fire prevention and rapid response to fires by utility operators, municipal managers and state regulators. It plans to offer these benefits through advances in remote sensing, wireless communication, power system security analysis and optimization.

“Our work comprises two interrelated research thrusts,” Pal says. “The first one focuses on developing sensor installations that can operate almost perpetually in distant areas. These ‘fit and forget’ nodes or suites of sensors need to be self-sustaining.”

Designing these sensor suites is the work of co-principal investigators Jennifer Blain Christen, an associate professor of electrical engineering in the Fulton Schools, and Umit Ogras, an associate professor of computer engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“Making these devices self-sustaining means harvesting energy from solar cells or coupling from power lines. But those capacities are not very generous, so we still need to be conservative with energy consumption,” Ogras says. “Our idea is to implement an innovative, hierarchical sensor system. It will divide the various sensors of each unit into several levels according to their power consumption.”

Pal says the team will leverage prior environmental sensing research that Ogras conducted as an assistant professor at the Fulton Schools, when he won a Young Faculty Award from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA.

“This hierarchy of sensing systems will be housed inside a closed box for protection against the environment,” Pal says. “These sensor suites will also need a reliable communication system because we’re talking about isolated installations. We need to consider where we place them, and how often they should communicate with the central system. These are some of the issues we’re exploring in the first thrust of the project.”

The focus of the second thrust is the power grid itself. Which specific types of information do these sensor suites need to provide in order to aid more reliable and resilient grid operations? And once provided, how can that information facilitate better decision-making? Pal will be working with co-principal investigator Line Roald, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, to look at both preventive and corrective decision-making.

“The preventive aspect aims to lower the risk of a wildfire initiated by the electric grid itself. For instance, hot and windy conditions in a given location might call for pre-emptively de-energizing power lines there,” Pal says.

Electric utilities already turn off power in response to wildfire conditions. But they do so across wide regions using a protocol called public safety power shutoff, or PSPS. These actions impact areas facing imminent danger, but also those with only a very small chance of experiencing a fire.

“Just to give you an idea, three million people in California lost power because of PSPS strategies in 2019,” Pal says. “We propose leveraging new data for a more selective approach in which power is cut only where and when it’s absolutely necessary.”

The corrective aspect of WARM’s second research thrust seeks to inform decision-making related to wildfires sparked by sources other than the electric grid, such as a lightning strike or a campfire that got out of control. How can data be applied to take grid-related action in a way that considers broader implications?

“Decisions need to account for different operating states. For example, the middle of a hot summer day is when people really need their air conditioners running. At that point in time, it might be best to keep the lines in service for as long as possible,” Pal says. “On the other hand, demand is lower at night because temperatures drop and most people are asleep. So, de-energizing some lines then may not cause a big problem. The key focus of our second thrust is to operate the power system across a spectrum of these situations.”

The last element of WARM’s work relates to policymaking, and it will be led by Elisabeth Graffy, a senior advisor for the Energy and Environment Directorate at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Graffy will focus on guiding future-focused decisions with the goal of enabling more targeted interventions. Examples include pre-emptively undergrounding power lines in areas of recurring high risk.

While the WARM project focuses on understanding, anticipating, measuring and mitigating wildfire risks associated with the electric grid, the sensor suites and risk management approaches developed could one day extend to guiding better strategies and tactics for addressing many contingencies. In cases of flooding, hurricanes and other disruptive events, the best decisions always demand the right data.