ASU students take on the Grand Challenges of the 21st century

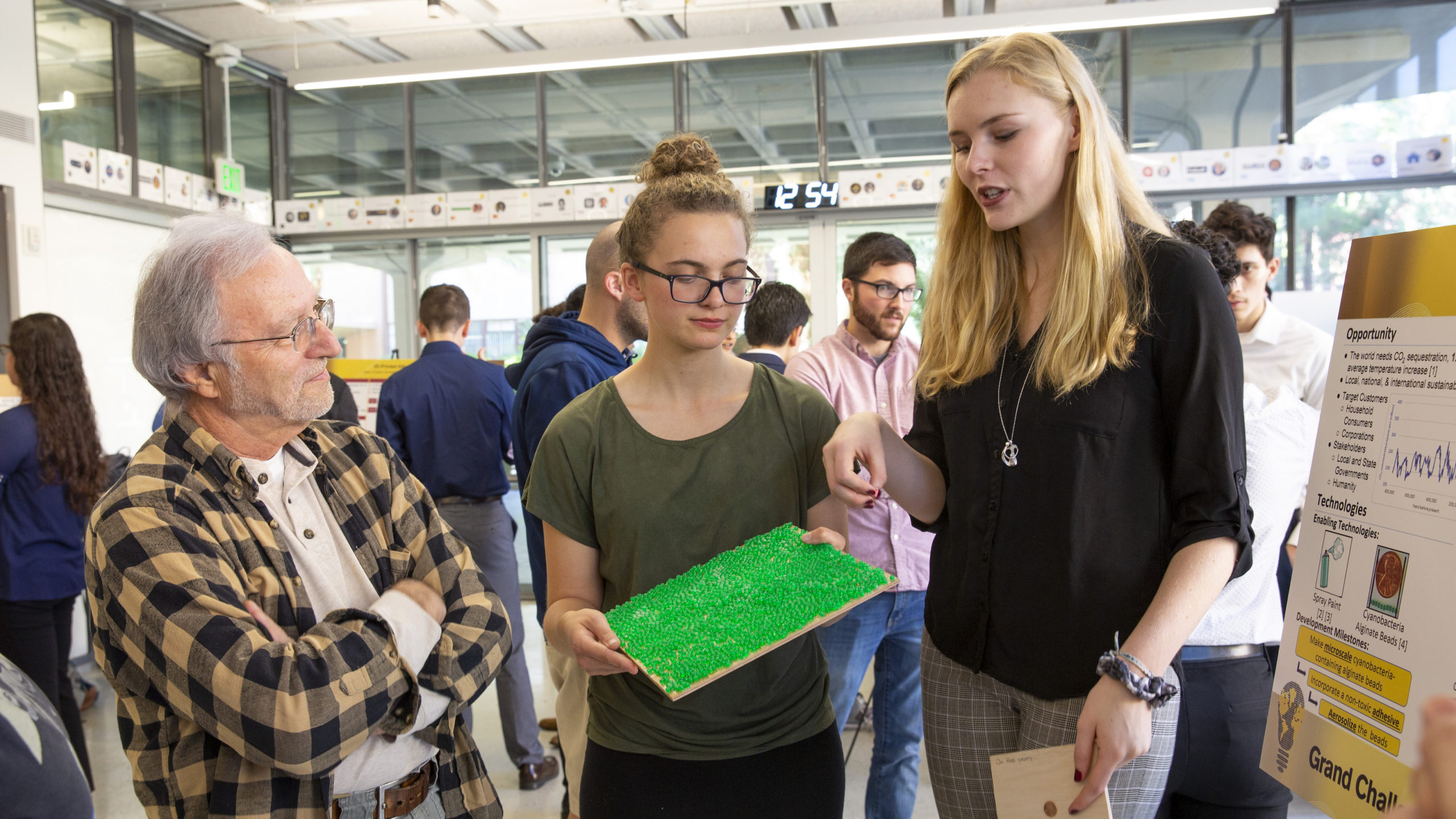

Above: Emily Hagood (right) and Audrey Schlichting (center) present their theoretical photosynthetic paint project at the Futuristic Solutions for the Grand Challenges poster presentation at the conclusion of the FSE 150 class. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

As the population grows and its needs and desires expand, sustaining civilization’s advancement is the greatest priority for the next generation of scientists and engineers. While engineering education programs prepare students for careers in their home country and region, 21st-century engineering has global implications.

In 2008, the National Academy of Engineering identified 14 Grand Challenges for Engineering in the 21st Century. Now enterprising students are working to develop futuristic solutions to those challenges.

The Grand Challenges Scholars Program was first proposed at the inaugural summit on the NAE Grand Challenges for Engineering at Duke University. Today more than 60 universities in the United States have a GCSP program, with each university creating their own approach to teaching students and defining their own curricula.

The Grand Challenges Scholars Program in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University encourages students to apply an entrepreneurial mindset to develop a creative solution to a problem within one of the Grand Challenges areas.

In the program, students are required to achieve five competencies to prepare them to address global challenges. The five competencies are: talent, multidisciplinary, viable business/entrepreneurship, multicultural and social consciousness.

Students who gain admission into the program work on curricular and co-curricular components to satisfy the program competencies. Grand Challenges Scholars focus their experiences on their chosen Grand Challenge through the themes of health, sustainability, security and joy of living.

Grand Challenges in the classroom

Students enroll in FSE 150: Perspectives on Grand Challenges for Engineering, a required course for the program. The class is taught by Amy Trowbridge, senior lecturer and director of the Grand Challenges Scholars Program at ASU, and it offers scholars the opportunity to develop an interdisciplinary appreciation for the Grand Challenges.

“GCSP provides students with the opportunity to gain the broader skillset and mindset they need to be the engineering leaders of the future and make a real difference in the world,” says Trowbridge. “Students can apply their technical skills to real-world problems through research and creative projects, while also developing an interdisciplinary systems perspective and the entrepreneurial mindset they need to solve complex global challenges.”

In the class, they apply an entrepreneurial mindset to develop a creative solution to a problem within one of the Grand Challenges areas, and to explore many aspects of its development and implementation. At the end of the semester, students in FSE 150 present their final course project, Futuristic Solutions for the Grand Challenges, through models and posters.

Developing futuristic solutions

One group of GCSP students at ASU decided to focus on the Grand Challenge of developing carbon sequestration methods. The team of Emily Hagood, a materials science and engineering major, Paul Larson, an aerospace engineering (astronautics) major, and Audrey Schlichting, an aeronautical management technology (professional flight) major, worked to design a theoretical photosynthetic paint that would be applicable to a variety of outdoor surfaces and could amplify the mitigating effects of natural photosynthesis on climate change.

This photosynthetic paint would be composed of microscale alginate beads, each encasing several cyanobacteria (unicellular organisms, similar in structure to chloroplasts in plants) that naturally convert light into energy.

A larger version of these cyanobacteria-containing beads is currently being used by Taylor Weiss, an assistant professor of environmental and resource management in the Fulton Schools, in research related to bioplastic production. The alginate beads both contain and limit the growth of the bacteria so their energy can be diverted to performing photosynthesis.

“For several weeks, we considered how to artificially mimic photosynthesis,” says Hagood. “Then, I read an ASU Now article on Dr. Weiss’s research, and I mentioned it to my group during class. We decided to pivot, utilizing natural photosynthesis in our theoretical technology. From that point on, everything just clicked, and we were able to conceptualize this technology and the barriers that pose challenges to its development.”

While there still are technological limitations impeding the development and the widespread implementation of this technology, Hagood would love to see the conceptual technology of photosynthetic paint advance to viability in the next couple of years.

Finding ways to tackle climate change is just one of the ways GCSP students are conceiving creative solutions

Maya Eleff, a biomedical engineering major, and computer science students Brightan Hsu and Cyrus Hunter worked on an implantable microelectrode system that stimulates the brain in a grid pattern to assist people with extreme vision loss.

In another project, computer science majors Raymond McDaniels and Bryan Alfaro partnered with electrical engineering major Kenneth Smith and manufacturing engineering major Richard Nguyen on their idea of creating self-healing roads. Their plan is to create a new asphalt mixture that utilizes bitumen (asphalt) and steel fibers that will “heal” roads when a heating trailer passes over the top of it, minimizing the need for expensive road repairs.

GCSP gives students the flexibility to direct their learning toward the problems they want to solve. Every component of the program enables and supports students to do a deep dive into the concepts, the research and the opportunities that interest them most.

“I love the focus on solution-oriented, service-based exploration,” says Hagood. “In GCSP, instead of just studying or admiring a problem, I have had the chance to consider, research and brainstorm the details and impacts of new and existing solutions to global issues. GCSP is purpose-driven with the goal of improving people’s lives.”

Current Fulton Schools undergraduate students and incoming first-year students are able to apply for the Fulton Schools Grand Challenges Scholars Program.

Connecting the entrepreneurial experience

As one of the five competencies, entrepreneurship is a key component of the Grand Challenges Scholars Program. For three weeks this past summer, ASU hosted 25 GCSP students from around the country for the GCSP Entrepreneurial Experience camp.

The GCSP Entrepreneurial Experience was developed as part of Fulton Schools’ efforts with the Kern Entrepreneurial Engineering Network, which focuses on helping students to develop an entrepreneurial mindset.

“This program was inspired by a desire to provide opportunities for students within the national GCSP community to connect with each other and collaborate on solving Grand Challenges-related problems,” says Amy Trowbridge. “I also recognized that at some institutions entrepreneurial opportunities are limited to coursework or starting a business venture, so I saw this as an opportunity to provide GCSP students nationwide with a different type of experience.”

Each year the camp focuses on one of the four themes, and in 2019 the theme was sustainability. In 2020, the camp will focus on health.

At the camp, students form groups to create a project and compete in a pitch competition at the end of the three weeks.

Cindy Rogel, a third-year materials science and engineering student in the Fulton Schools, was a member of the winning team known as Citrus Solutions. They took on the challenges of providing clean drinking water. Specifically they addressed what to do with organic waste by repurposing orange peels and other fruits from juice companies into a filter that would extract metallic contaminants from water.

“I had taken engineering classes like FSE 100, FSE 150 and Engineering Projects In Community Service,” says Rogel, “but once I got into this camp I was finally learning the full scope of the entrepreneurial mindset. Learning how engineering plays into it made me understand what an engineer needs in order to make a successful project that can make an amazing impact to our communities.”

Keene Patarakun, an ASU mechanical engineering major, and his LifeSoil teammates, who came from the University of Oregon, University of Idaho and Worcester Polytechnic Institute, took second place with a project that specialized in composting systems.

Patarakun appreciated being able to work with his team and learn how a real-world team would function.

“Students within ASU may learn mostly the same content in the same fashion, as a consequence of taking the same classes. Although each person will have unique skills to bring to the table still, the underlying principles might be the same,” says Patarakun. “I think it’s very, very important to partner with students from other schools because they provide the diverse perspectives and skills needed to make a project successful.”