Striving for big steps in prosthetic hand technology

Prosthetics have advanced from the simplistic apparatuses of only several decades ago to today’s complex interfaces of devices and biological systems that are designed to resemble missing body parts and replicate their functions.

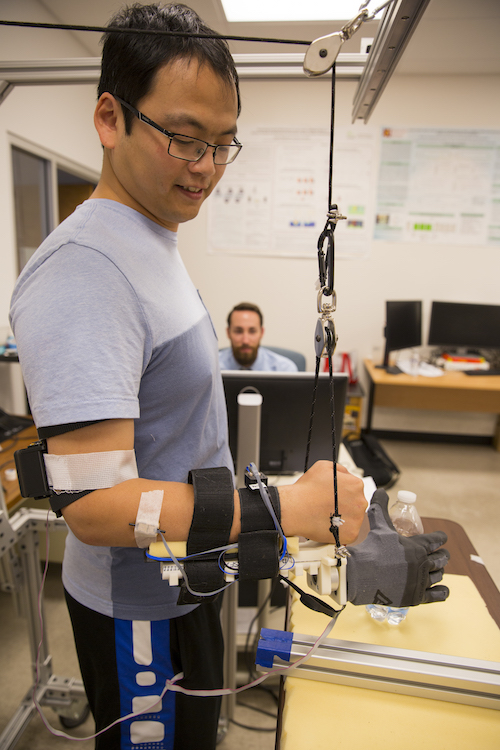

Assistant Research Professor Qiushi Fu is shown demonstrating a synergy-based prosthetic hand, called the SoftHand Pro, to grasp a bottle, while data is being recorded by a neuroscience doctoral student Patrick McGurrin (in background). The prosthetic hand movement is controlled by electrical signals recorded on the surface of the forearm, and force feedback is delivered to the cuff worn around Fu’s arm. Photographer: Jessica Hochreiter/ASU

But researchers are far from satisfied with that progress.

They have set their sights beyond making refinements and improvements. They are eyeing big leaps forward in expanding the capabilities of prosthetics technologies.

Projects in which Arizona State University engineers are collaborating are among those aiming at nothing less than revolutionary steps in hand prosthetics.

Professor Marco Santello and his research colleagues want to help break through the functionality barriers that still persistently burden people with artificial hands.

Santello is the director of the School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering, one of ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, and a neurophysiologist who directs the Neural Control of Movement Laboratory at the university.

Despite all the technological advances to date, he explains, there remain several barriers to be overcome to empower individuals who have lost limbs to regain a level of function with prostheses that they can be fully satisfied with. One such barrier is lack of sensory feedback.

“Users of commercially available prostheses still must always look at what the artificial hand is doing to be able to properly control it, because current technology cannot fully compensate for the lack of feedback when, for instance, a user is touching or manipulating an object,” Santello says.

Seeking seamless integration of technology and nervous system

Working with researchers at the Mayo Clinic, the Italian Institute of Technology and Florida International University, Santello and ASU colleagues Qiushi Fu and James Abbas are applying some of the latest advances in bioengineering, robotics and brain-machine interface systems to development of prosthetic hands that enable users to feel sensations by which they can judge how much or how little force to exert in gripping, lifting, moving and holding particular objects.

With new technologies that directly connect with the body’s nervous system, they hope to provide feedback by using mechanical or electrical stimuli that can send task-relevant information to the brain by exerting pressure on the skin or stimulating peripheral nerves. Such a feedback loop would give artificial hand users the critical information to enable performance of a wide range of normal daily living activities.

The challenge is to construct a seamless integration of the nervous system with a myoelectric prosthetic hand — one that is controlled by electrical signals generated naturally by one’s muscles.

It’s a task that requires teams of researchers with a broad range of complementary expertise in various branches of engineering, neuroscience and medical science.

Santello’s key collaborators include:

- Qiushi Fu, a Fulton Schools assistant research professor with expertise in human hand function and control, and in bio-inspired robotics

- Rosalind Sadleir, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering in the Fulton Schools and director of the Neuro-Electricity Laboratory

- James Abbas, a Fulton Schools associate professor of biomedical engineering and director of the Center for Adaptive Neural Systems

- Kristin Zhao and Karen Andrews in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Zhao is the director of the Assistive and Restorative Technology Laboratory. Andrews directs the Amputee Clinic

- Ranu Jung, professor and chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering and director of the Adaptive Neural Systems Laboratory at Florida International University

- Antonio Bicchi, a professor of robotics with University of Pisa in Italy and Sasha B. Godfrey with the Italian Institute of Technology

Ambitious research goals are drawing support

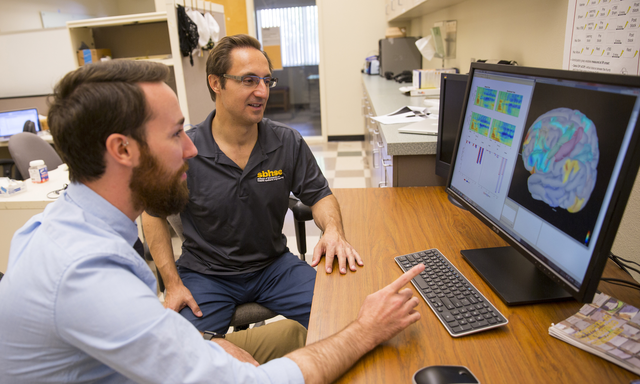

Professor Marco Santello (at right), director of the Neural Control of Movement Laboratory at ASU, is leading research that aims to develop advanced prosthetic hands that function and feel like natural hands. He is pictured here with neuroscience doctoral student Patrick McGurrin, discussing brain activity data collected during performance of dexterous object manipulation tasks for prosthetic hands. Photographer: Jessica Hochreiter/ASU

In various combinations, they are fellow principal investigators or co-principal investigators on three prosthetics research projects for which Santello has been awarded grants in the past two years.

The National Institutes of Health have been funding work to identify strengths and weaknesses of a “synergy-based artificial hand” — designed by Bicchi and collaborators — through a variety of tests involving grasping and manipulation tasks. Part of this work has been carried out at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Research aimed at optimizing the integration of sensory feedback into prosthetics to control movement and manipulation is supported by a joint ASU-Mayo Clinic Team Science Seed Grant. The project focuses on testing non-invasive feedback systems for hand prostheses and user’s adaptation to integrating artificial feedback with prosthesis control.

A project funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, a part of the U.S. Department of Defense, teams Santello, Abbas and Fu with Jung and her team at Florida International University. Jung, Abbas and their team have developed a new neural-enabled system that uses implanted electronics to provide tactile sensation to amputees based on information derived from sensors on a prosthetic hand.

Santello and Fu will team with Jung and Abbas to test the “synergy-based artificial hand” using the implanted neural-enabled system for sensory feedback.

New national center could aid the endeavor

Through these varied but related endeavors, Santello sees the potential for a new wave of easier-to-control prosthetics technologies with more durability and more robust functionality.

For people using artificial hands that means having prosthetics that feel real — that are highly sensitive to pressure, force, vibration and texture, with a full range of movement and grasping ability, and controlled through the same natural intuitive actions and reactions that we use to control our muscles.

“The big hurdle is to fully and effectively integrate the body’s systems with prosthetic systems, which necessitates getting the body to accept that integration with the technology,” Santello says. “There are many dimensions to the problems that need to solved to accomplish this.”

More help in solving those problems could come by way of Santello’s role as the ASU principal investigator in the BRAIN Center, (Building Reliable Advances and Innovation in Neurotechnology), a recently established National Science Foundation Industry/University Cooperative Research Center.

Led by ASU and the University of Houston, the BRAIN Center focuses on developing and testing new neural technologies with the potential to dramatically enhance patient treatment and functional capabilities.

The work supported by the BRAIN center, which will involve industry and clinical partners, includes testing technologies designed to improve a wide range of the sensory, motor and cognitive functions, such as those that researchers want to put into new kinds of prosthetic devices.