Building biofabrication systems to transform health care

Fulton Schools researchers combining medical imaging and tissue engineering skills to advance regenerative medicine

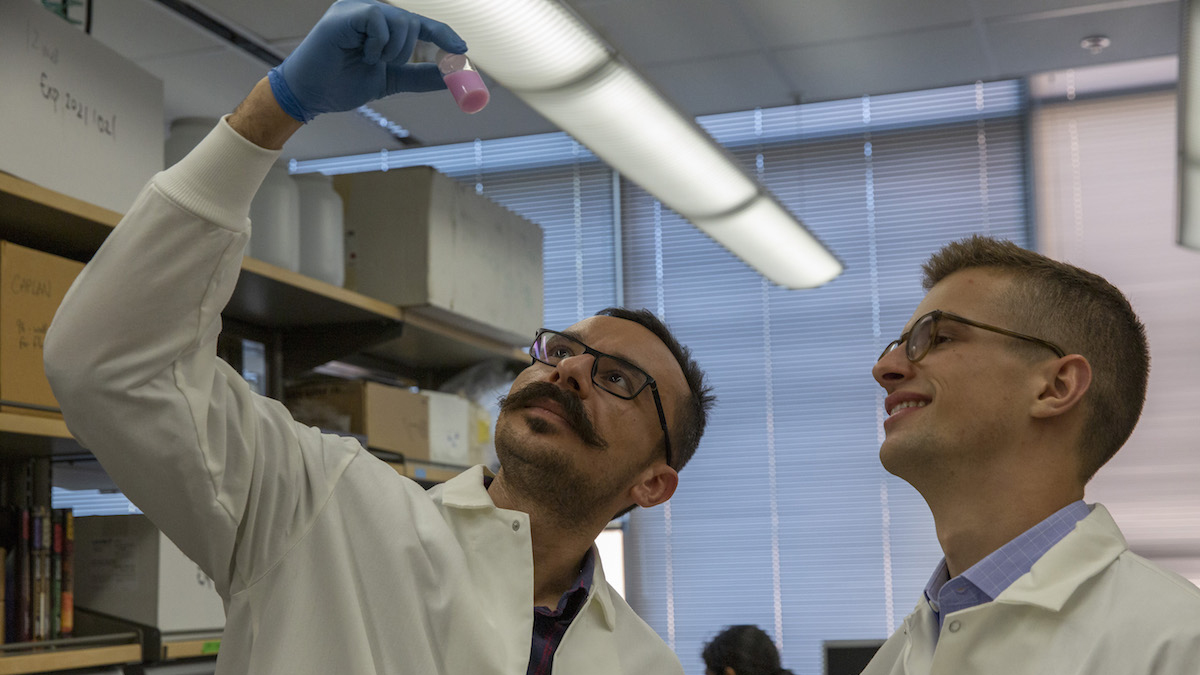

Above:Doctoral student Babak Moghadas and research scientist Jacob Knittel examine a small bottle of pink oxygen sensing nanoprobe solution. The nanoprobes are used to monitor the health of engineered cells during the manufacturing process. The monitoring is designed to ensure the cells will function as expected in regenerative medicine applications. Photographer: Connor McKee/ASU

Regenerative medicine promises to revolutionize medical care at its most basic foundations. But fulfilling its potential requires advances in multiple branches of science and engineering.

Among the field’s fundamental challenges is developing methods of engineering or regenerating human cells, body tissues and organs that can restore healthy biological functions.

Arizona State University Associate Professor Vikram Kodibagkar and Assistant Professor David Brafman are at work on integrating newly-developed imaging probes into the manufacturing of engineered cells — with the ultimate goal of contributing to effectively moving regenerative medicine products from the laboratory to patients’ bedsides.

That’s the overarching mission of the Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute, which supports BioFabUSA, a U.S. Department of Defense-funded biomanufacturing consortium that is creating the biofabrication systems for large-scale manufacturing of engineered tissues and organs.

In their BioFabUSA-related efforts, Kodibagkar and Brafman, who are both on the biomedical engineering faculty of ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, are focusing on the sensing and monitoring aspects of the manufacturing process.

“The idea is to make sure manufactured cells are healthy and capable of doing what they are designed to do” in diagnosing and treating diseases and other physical disorders, Brafman says.

Research at Arizona State University in collaboration with the national BioFabUSA consortium is aimed at advancing regenerative medicine. The work is led by Assistant Professor David Brafman (fourth from left) and Associate Professor Vikram Kodibagkar (third from right). Their work is aided by (from left) doctoral student Gayathri Srinivasan, research scientist Jacob Knittel and undergraduate Tanner Henson from Brafman’s lab, and (from right) postdoctoral research associate Christopher Rock and doctoral student Babak Moghadas from Kodibagkar’s lab. Photographer: Connor McKee/ASU

Their objective is to produce engineered body tissues in a way similar to how automobiles are made on a conveyor-belt setup.

As they explain it, car manufacturing starts with raw materials like steel, plastic, rubber and glass to build the vehicle’s frame. Then the basic operational components — the electronics, steering, braking and exhaust systems and so on — are assembled and compatibly integrated to create an automobile.

What the ASU researchers emphasize is also critically important to the assembly process are exacting methods to ensure that during the assembly all those parts will function reliably once the final product is completed.

For Kodibagkar and Brafman’s cell-making undertaking, nanoprobes are the key to ensuring manufactured tissues are operating as the should. Nanoprobes obtain the real-time measurements that indicate the health and vitality of engineered cells and tissues during the manufacturing process.

The nanoprobes are “like an onboard computer,” Kodibagkar says. “Think of them as spies or reporters that can tell us not only how the manufacturing process itself is working, but even afterward, when cells are delivered to patients, we can still get accurate information about the health of the transplant.”

The specific purpose of the imaging probes in their project is to accurately measure the oxygenation and acidity (or pH) in engineered cells and tissue. Oxygenation and pH levels are “great indicators of whether cells’ metabolism is functioning in a healthy fashion,” Kodibagkar says.

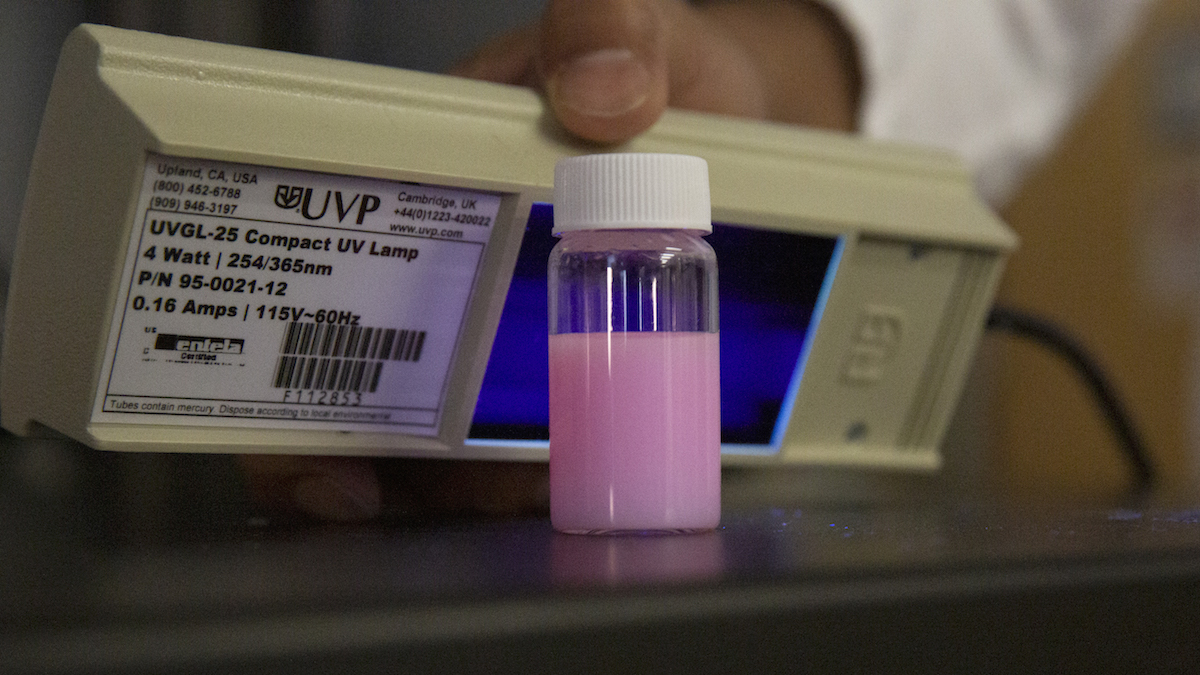

The nanoprobes are carefully balanced concoctions of chemicals, mixed with oil and water emulsions. Some are capable of sending signals that can be interpreted by magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. Others can fluoresce (light up) so that they are detectable by medical optical imaging devices. Both methods reveal the health status of cells and tissues.

The primary ingredient in the oxygenation sensing nanoprobes is siloxane, a chain of hydrogen, carbon, silicon and oxygen atoms. The hydrogen atoms help the nanoprobe produce the signals that are influenced by oxygen and can be picked up by an MRI scanner.

The point of all this is to build what Kodibagkar and Brafman describe as “3D tissue constructs” that can be integrated with imaging probes to provide more precise readings of cells and tissues and paint a picture of what’s happening around them in their “local microenvironments.”

So far, they have developed several nanoprobe-based imaging technologies and are aiming to make more.

Their processes also rely on the abilities of pluripotent stem cells, also called master cells because of their ability to generate cells from any layers of body tissue to produce the specific cells or tissues the body might need to repair itself.

Each of BioFAbUSA’s major research thrusts will benefit from the combined expertise of Kodibagkar and Brafman, both of whom teach in the School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering, one of the six Fulton Schools.

The scope of their research efforts encompass generating and monitoring engineered cells and tissues, scaling up both of those processes and devising ways to safely preserve and transport the engineered biomaterials for implantation into patients.

Most importantly for their work in producing those cells and tissues, Brafman says, “we are not taking them out of the manufacturing line or disrupting the process. It’s noninvasive and nondestructive, which is critical to the success of a biomanufacturing pipeline.”

Kodibagkar and Brafman see the potential for engineered cells to boost advances in cell therapies, such as those used to treat diabetes and even cancer, as well as to improve weakened immune systems.

Regenerated cells and tissues could also be reprogrammed to aid research to develop new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, cardiac problems, tumors and brain injuries.

“They could be used to do further studies in disease mechanisms and disease progression,” Brafman says. “You can make tissues that mimic the tissues in different parts of the body, so that you can better understand the biology involved in the way the brain or the heart works.”

Arizona State University biomedical engineers David Brafman and Vikram Kodibagkar are leading research aimed at integrating new imaging tools into manufacturing processes for cells and body tissues needed to realize the high hopes for regenerative medicine. A part of that endeavor involves use of an oxygen sensing solution (pictured here) that helps to determine if engineered cells and tissues are healthy and functioning effectively. Photographer: Connor McKee/ASU