ASU brings the world of engineering to local high schools

Above: The EPICS High Virtual Olympiad outreach event hosted by the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University challenges high school students to think like engineers to generate solutions to community problems. In the most recent event, students worked with the ASU chapter of Engineers Without Borders to come up with their own solutions to a real challenge the organization faced in rural Kenya. Graphic courtesy of Shutterstock

Phoenix-area high school students were virtually transported to rural Kenya to solve a real-world engineering challenge through an Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University outreach program.

The Engineering Projects in Community Service program for high school students, known as EPICS High, recently hosted its first three-week EPICS High Virtual Olympiad with the ASU chapter of Engineers Without Borders. The experience was designed to introduce STEM skills and an engineering mindset to high school students.

The event helped more high school students learn engineering design skills than in past events and enabled the Engineers Without Borders undergraduate students to stay involved even as international travel has been limited due to the pandemic.

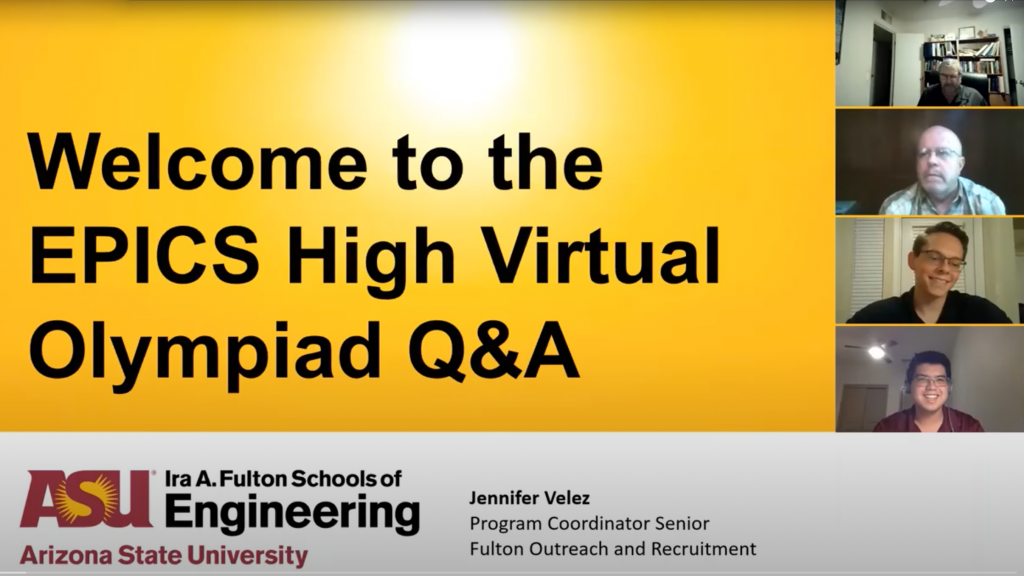

“Through the EPICS High program, we aim to provide students with experiences that mimic the work that real engineers do, and this year’s Olympiad has succeeded in that,” says Jennifer Velez, coordinator senior of the K-12 Engineering Education and Outreach team who organized the EPICS High Virtual Olympiad. “The feedback from teachers, students and our partners in Engineers Without Borders has been overwhelmingly positive.”

Two programs combine for new outreach opportunity

High school outreach has not typically been the focus for the ASU chapter of Engineers Without Borders, says Alex Owen, a third-year civil engineering major and the chapter’s president.

“However, during this time of virtual everything, building early STEM awareness and understanding has been one of our top priorities,” Owen says.

So, in November, as a new way of giving back to the community, Engineers Without Borders got involved with the EPICS High Virtual Olympiad. Owen and other members modified a past Engineers Without Borders project and put their members to work as mentors in the EPICS High program.

The original Engineers Without Borders project involved bringing a reliable source of drinking water to a rural village in western Kenya. While rain is plentiful during some parts of the year, others are marked by extremely dry conditions. Old reservoirs and water sources had fallen into disrepair or were unreliable, so women and girls walked miles to collect water from faraway sources each day, and many sources of water were contaminated. With severely limited resources, members of Engineers Without Borders were challenged to maximize time and their budget to make an impact for the village’s 500 residents.

A new Olympiad experience

Presented with the same circumstances Engineers Without Borders members had faced in Kenya, this design challenge was much more demanding than what EPICS High Olympiad students faced in previous years. The extended timeline also offered a deeper learning experience with more opportunities to think like an engineer and solve a problem many people around the world are facing.

Before the pandemic, EPICS High Olympiad events brought hundreds of students to ASU’s Tempe campus for a rapid prototyping experience over the course of a single day. Students were given a challenge and requirements for a solution, and they would talk with undergraduate students and industry professionals who serve as their “customers.”

It’s a good “toe-dipping experience” to human-centric design, says Tirupalavanam Ganesh, a Tooker Professor and assistant dean of engineering education in the Fulton Schools who was a judge in the most recent EPICS High Virtual Olympiad.

Like any engineering challenge, the event organizers had to work within some boundaries. Going virtual meant there’d be some concessions, but it also presented some opportunities. While the high school students didn’t get to visit the ASU campus, transportation and cost barriers were removed, which allowed 250 students from six high schools to participate. Extending the event across several weeks also helped students get a deeper understanding of the problem and the potential solutions.

“Giving students who are in high school this really unique opportunity to think about a problem space that’s real, has evidence and narratives of the people’s challenges, and then solve it, is really quite remarkable,” Ganesh says. “The students took the problem to heart. They put in the effort.”

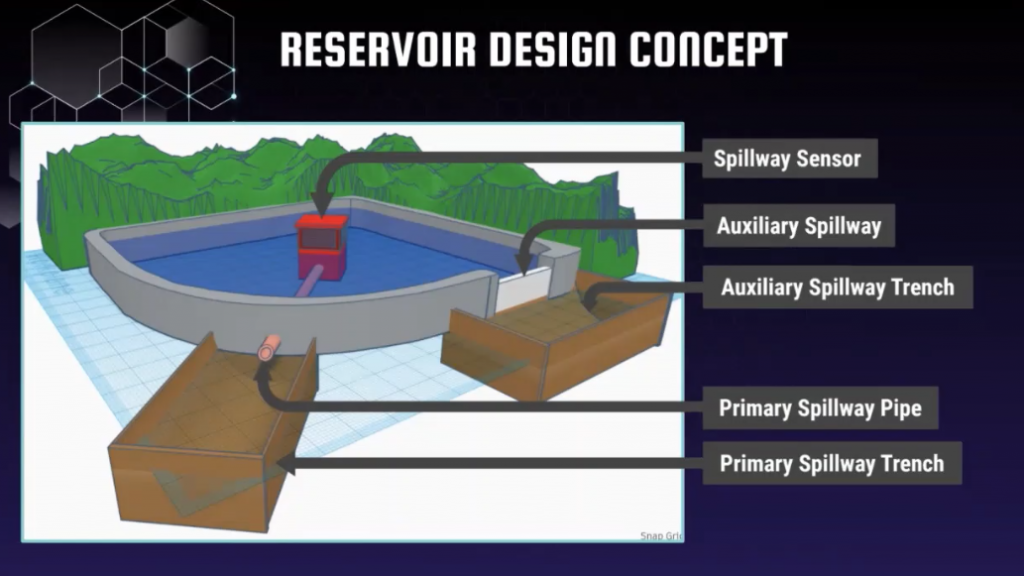

High school students from Gilbert Classical Academy on the “Repair the Reservoir” EPICS High Virtual Olympiad team designed a way to fix the village’s reservoir to store water during times of drought. Image courtesy of Jennifer Velez

A valuable, collaborative experience

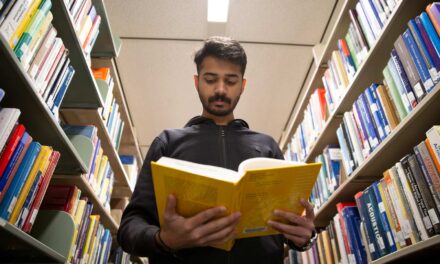

Lizzie Beistle, a junior at Gilbert Classical Academy, didn’t think she was particularly interested in engineering when she first signed up for EPICS High, but that all changed once she was pushed out of her comfort zone and began to think critically about real-world problems.

“From the moment our first brainstorming session began, we were hooked,” she says of her team, named Repair the Reservoir. “The challenge EPICS presented to us was frustrating, to say the least, and every single one of us was desperate to find a solution. We spent countless class periods and late-night calls trying to figure it out until we had this one glorious ‘aha!’ moment.”

That idea — repairing and reinforcing the village’s earthen reservoir dam with concrete — led to their selection for the next level of the competition as well as a first place Olympiad finish and Impact Award, given for the project with the most potential to help the community.

Beistle says she found the budgetary, resource and labor constraints of working in rural Africa to be the most interesting part of the challenge.

“We were constantly thinking about if we could afford that, how things would be transported, if villagers could feasibly build our design and more,” Beistle says, “which ended up teaching us not only how to think like engineers but also how to predict problems before they arise.”

Advice from a professional engineer

Greg Rodzenko, the Engineers Without Borders industry mentor and former land development engineer and City of Glendale city engineer, shared the real experience of working on impactful and challenging international projects.

Rodzenko got involved with ASU’s Engineers Without Borders chapter completely by accident in 2010. A coworker invited him to go on a project trip to Ecuador because the students needed to be accompanied by a professional engineer, and he has been involved ever since. He has also been involved in ASU’s EPICS program for five years, leading projects on the Navajo Nation.

Rodzenko has always been passionate about fieldwork since he advocated for field labs in graduate school in the 1970s and he continues to inspire students with hands-on projects.

“When you put interesting projects in front of curious humans, good things happen,” Rodzenko says.

Rodzenko was one of the industry mentors who accompanied the ASU Engineers Without Borders students to Kenya between 2012 and 2014 when they traveled there to solve some of the area’s water challenges.

“[The Kenya water challenge] is not just a high school student problem. My learning curve was equally steep and humbling,” he says. “It’s fascinating to watch the ‘lightbulbs’ turn on — it’s an intellectual process but you also see their emotions when they ‘get it’ or have an ‘aha!’ moment.”

Regents Professor and Ira A. Fulton Professor of Geotechnical Engineering Edward Kavazanjian, Engineers Without Borders ASU chapter industry mentor Greg Rodzenko, student president Alex Owen and Engineers Without Borders member Matthew Kimball answer questions about the real situation they faced when addressing water needs in Kenya during an EPICS High Virtual Olympiad Q&A session with the high school participants. Image courtesy of Jennifer Velez

Creative problem-solving to impact people’s lives

In second place, Rooftop Catchment, another team of students from Gilbert Classical Academy developed a solution to collect and filter rainwater.

As a judge, Ganesh was particularly impressed by the research and mathematical calculations the students did to understand the potential yield of rain capture into a communal basin.

The When In Rome team from Red Mountain High School also looked into repairing the local reservoir.

The solution the Engineers Without Borders students developed during their years on the project involved capping earthwork dams with concrete to keep them from being breached and damaged. They also implemented a rainwater harvesting system at a nearby college.

Through question-and-answer and debrief sessions during the event, Rodzenko, Engineers Without Borders student Owen, Engineers Without Borders faculty mentor and Regents Professor and Ira A. Fulton Professor of Geotechnical Engineering Edward Kavazanjian and others relayed the actual experience of working in rural Kenya.

“Having the opportunity to mentor and judge the students’ presentations sharpened my own engineering skills and it left me very encouraged for the incoming STEM students,” Owen says.

“Looking back to my own high school and middle school days, I lacked the chance to participate in any events like this,” he says. “I hope to stay involved in more outreach because STEM education is important for all students.”

Skill-building for any future

While technical skills were necessary to complete the projects, it’s not the only thing the engineers needed to help communities. The EPICS High and EPICS High Virtual Olympiad experiences are helpful for future engineers and other professionals alike.

“[Students learn] how to think. It’s a key part of becoming a professional problem-solver, engineer or scientist,” Rodzenko says. “These projects are an interesting and useful way to learn how to do research, how to organize information and how to present information to others.”

Logan Skabelund, a senior at Red Mountain High Schools, is planning to study mechanical or electrical engineering at the Fulton Schools this fall. He is among approximately 26 of the participating students to be admitted into the Fulton Schools in the fall.

Skabelund got involved in EPICS High to be able to solve a real-world engineering problem, and the EPICS High Virtual Olympiad was like a “mini senior capstone project” that showed him how engineering projects operate.

“It’s a different experience than working in a classroom environment because your solutions may actually be used and have a real effect in the world,” Skabelund says. “[Through EPICS High] I’ve learned so much about the engineering and manufacturing process.”

Beistle plans to attend Dartmouth and pursue studies in government, history, economics, quantitative social science and sociology.

“I think this just goes to show that the EPICS program isn’t just for ASU hopefuls and future engineers,” Beistle says. “It can be very much enjoyed by students interested in all kinds of fields.”