ASU alum advances computing, networking, storage systems and the world

Robert Garner

Arizona State University alumnus Robert Garner is energized by a desire to make a difference. Throughout his career, he has harnessed the power of electrical engineering and computer science coupled with a strong work ethic to fuel the expansion of computing and the internet.

Garner has contributed to some of computer engineering’s most impactful advances to power and interconnect the world, but his interest in computing developed before he enrolled in what was then the engineering department at ASU.

“I was a classic nerd as a young kid,” said Garner, who has more than 40 years of engineering experience. “At that time, I could imagine computers controlling nearly anything mechanical in the world.”

Garner’s passion for science and engineering came from his father, who had a degree in aeronautical engineering and worked at AiResearch, which later became Garrett AiResearch and now is a division of Honeywell. In grade school, Garner devoured his father’s physics textbooks and attended workplace meetings with him. He had other interests too but wanted to pursue a field with the potential for real-world impact. That’s why he chose to follow his passion for electronics.

In 1972, Garner decided to study at ASU in large part because of its professors, who supported and nurtured him both as a high school and college student.

Professor Gregory Nielson in the mathematics department and Professor Barry Leshowitz in the psychology department took him under their wings. Garner helped Nielson develop his pioneering 3D surface-viewing software and Leshowitz conduct auditory recognition experiments using a minicomputer.

Garner’s strong work ethic took shape as he showcased an unparalleled dedication to his work with these professors. He often worked in Nielson’s office late into the night, including weekends.

“I was grateful ASU professors went out of the way to help high school students,” said Garner. “They were committed, enthusiastic, patient and definitely serious about their research.”

After receiving a bachelor’s degree in engineering from ASU and a master’s degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University, Garner secured a position as a hardware engineer at Xerox’s System Development Division, the go-to-market companion to the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in Palo Alto, California. In the mid-1970s, Xerox PARC pioneered the modern networked personal computer as it’s known today.

Garner had an on-campus interview with Bob Metcalfe, who had co-invented the Ethernet at PARC. Landing the job was a result of the long hours Garner devoted to advancing Nielson’s surface-viewing software, maintaining a high GPA and spending time in extracurricular activities. Garner also credits “the non-siloed, interdisciplinary and accessible nature” of his education at ASU.

Serendipitously, unbeknownst to Garner, Nielson had consulted at PARC in the mid-1970s and graciously penned a positive reference letter.

“You should take every job or activity, no matter how small, seriously,” said Garner. “Your connections coupled with working hard are key to new job opportunities.”

Working under Metcalfe and Bob Belleville, who would go on to manage the development of the Apple Macintosh, Garner co-designed the Xerox STAR Professional Workstation, the descendant of the PARC Alto and the first commercial networked personal computer.

To bring its new personal interactive and networked features to market as quickly as possible, in Silicon Valley style, Garner again found himself happily working late into the early morning hours for many years.

“When building the Ethernet, we believed it would bring the world closer together,” said Garner. “I’ll never forget when I first put an Ethernet in my house. Stunned, I couldn’t believe it had gone from an obscure engineering project to worldwide adoption.”

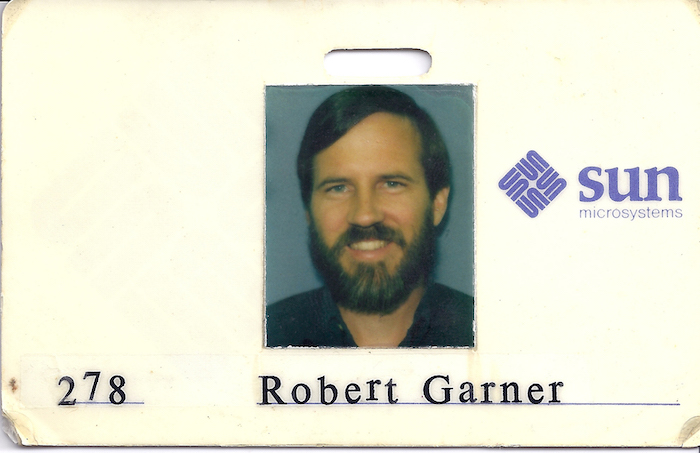

Robert Garner’s Sun Microsystems badge from 1984.

Later in his career, Garner was recruited by the then-startup Sun Microsystems. For nearly 15 years, he made substantial contributions to the advancement of microcomputers. These advancements fueled the company’s growth from a small startup to $1 billion in annual sales in a few years.

Garner served as the lead architect of one of the earliest Reduced Instruction Set Computers, known as SPARC, or Scalable Processor Architecture. He co-designed the Sun-4/200 Workstation, the first SPARC system. He also helped hire and build subsequent teams that designed leading-edge microprocessors.

“SPARC fueled the most powerful and robust workstations and servers in the market for about 10 years,” said Garner. “It transformed the engineering workstation and internet server marketplace at the time.”

Compared to the Complex Instruction Set Computer processors at the time, SPARC computers ran about three times faster. In 2015, SPARC received the prestigious Milestone Award from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

After working as director of hardware engineering at Brocade Communications Systems — the startup that pioneered FibreChannel networks for storage subsystems — Garner tapped into his expansive network of colleagues and friends to land a job at the IBM Almaden Research Center.

At IBM, he co-designed an imaginative 3D scalable server prototype, managed the design team of a software-defined high-performance storage server known as the IBM Elastic Storage Server and managed the advanced development group for IBM’s General Parallel File System. Summit, an IBM-built supercomputer designed for use at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, utilizes the parallel and software-defined storage technology developed under Garner’s leadership. According to the TOP500 List, a ranking of the world’s fastest computing systems, Summit has been named the world’s most powerful computer this year. It’s the first time since 2012 the U.S. has claimed this title.

Garner retired in May, but he continues to work on a volunteer project started while at IBM. He leads a team of retired IBMers and younger non-IBM volunteers who have come together to restore two 1960s IBM mainframes, which are exhibited live at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. Since a mainframe weighs more than five tons, produces a racket and enthralls kids with its liveliness, it’s been nicknamed a “compusaur.”

In his free time, Garner enjoys mountaineering, backpacking, hiking, running and skiing. He also volunteers on the Advisory Board of Flagstaff’s Lowell Observatory.

Garner has had a long and fulfilling career, complete with a resume of impressive achievements, where his engineering leadership was instrumental to the advancement of computing, networking and storage. He has some valuable advice for fellow engineering students and alumni.

“You can’t do everything on your own,” said Garner. “Get to know a lot of people, hear them out for their ideas, opinions and intuitions, turn those contacts into friends and rely on your network for support. They can be instrumental in showcasing your hard work and dedication.”