A passion driven mission

Zeal for engineering and philosophy meld in Fulton Schools alum’s work to help guide the nation’s space exploration endeavors

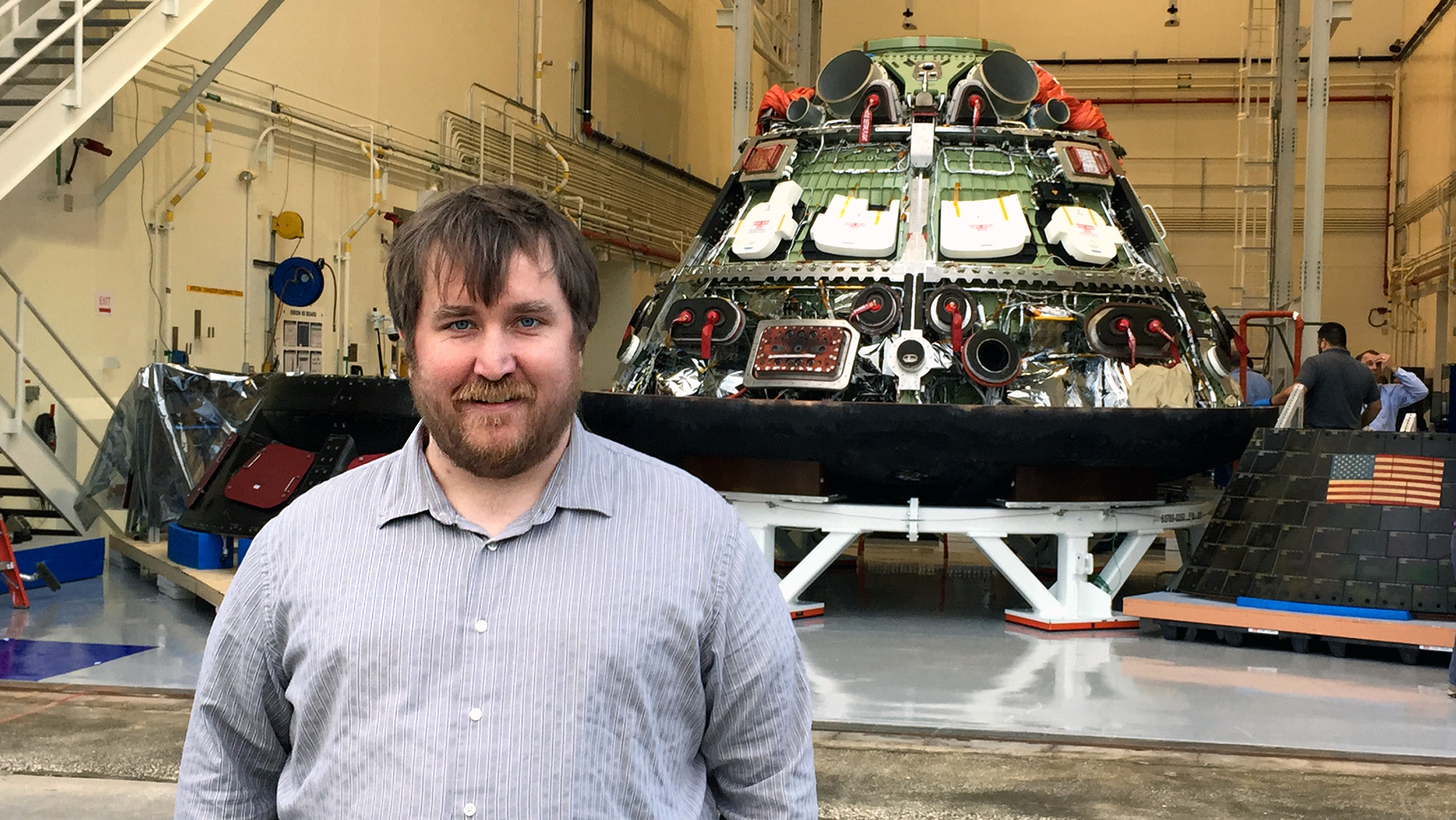

Above: Zachary Pirtle is pictured in 2015 in front of an Orion spacecraft after it was launched into a high energy Earth reentry as part NASA's 2014 Exploration Flight Test-1 mission. Pirtle observed the capsule being dismantled and evaluated. Such experiences have informed his academic writing about how engineers learn from real-world test missions, helping them to better design and improve systems engineering approaches to space missions. Photo courtesy of Zachary Pirtle

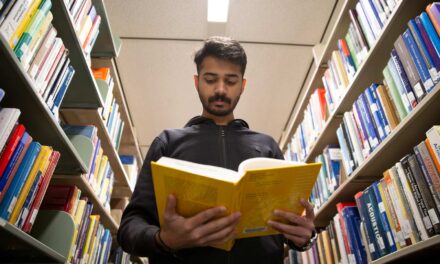

Zachary Pirtle recalls struggling with his choice of a major during his first year of studies in Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. He was following in his father’s career footsteps by enrolling in the mechanical engineering program, but by his second year was contemplating a change.

Two things prevented him from taking a different direction. He got an internship working in the aerospace division at Honeywell and he began taking courses in the philosophy of science.

Zachary Pirtle earned NASA’s Early Career Achievement Medal for his leadership in helping shape NASA’s deep space exploration programs. He draws on his NASA experiences to help further develop the scholarly foundations for a full-fledged philosophy of engineering. Photographer: Bill Ingalls/NASA

The internship showed him “how engineering works in the real world,” Pirtle says. The philosophy classes helped him view engineering from a broader perspective of its value in gaining new knowledge and insights and applying them in ways that best serve society.

“From that point, I was committed,” Pirtle says. “I wanted to be a philosopher of engineering. I wanted to get plugged into that kind of community and help create that field.”

That drive led him to become a respected student among his professors and later a leader in space exploration and policy at NASA.

Journey of a rising star

Pirtle’s aspirations necessitated a fifth year of undergraduate studies as a student in ASU’s Barrett, the Honors College, to earn bachelor’s degrees in both mechanical engineering and philosophy in 2007, followed by a master’s degree in civil engineering and environmental engineering two years later.

A decade later, in 2019, Pirtle completed work for a doctoral degree in systems engineering at George Washington University, or GWU, in Washington, D.C.

He had moved to the city in 2010 to join NASA and soon began working his way into more senior positions. The agency also funded his doctoral research. He is now an adjunct professor at GWU, where he has taught a graduate-level systems engineering course.

Recently, Pirtle was awarded the NASA Early Career Achievement Medal for “outstanding leadership in helping formulate NASA’s deep space exploration programs, with innovative application of the program management discipline.”

“I’ve been lucky to work on some of NASA’s most complex systems engineering problems and public policy issues involved in trying to shape our human spaceflight goals,” Pirtle says, “and because of the range of my undergraduate and graduate studies, I feel I can bring both technical knowledge and a philosophical approach to problem-solving in these different areas.”

Pirtle’s other achievements have included co-chairing the Forum on Philosophy, Engineering and Technology in 2018 at the University of Maryland, College Park, featuring researchers who focus on studying the nature of engineering design, knowledge and ethics. The academic papers from the conference led to the recent publication of the anthology “Engineering and Philosophy: Reimagining Technology and Social Progress,” which Pirtle co-edited.

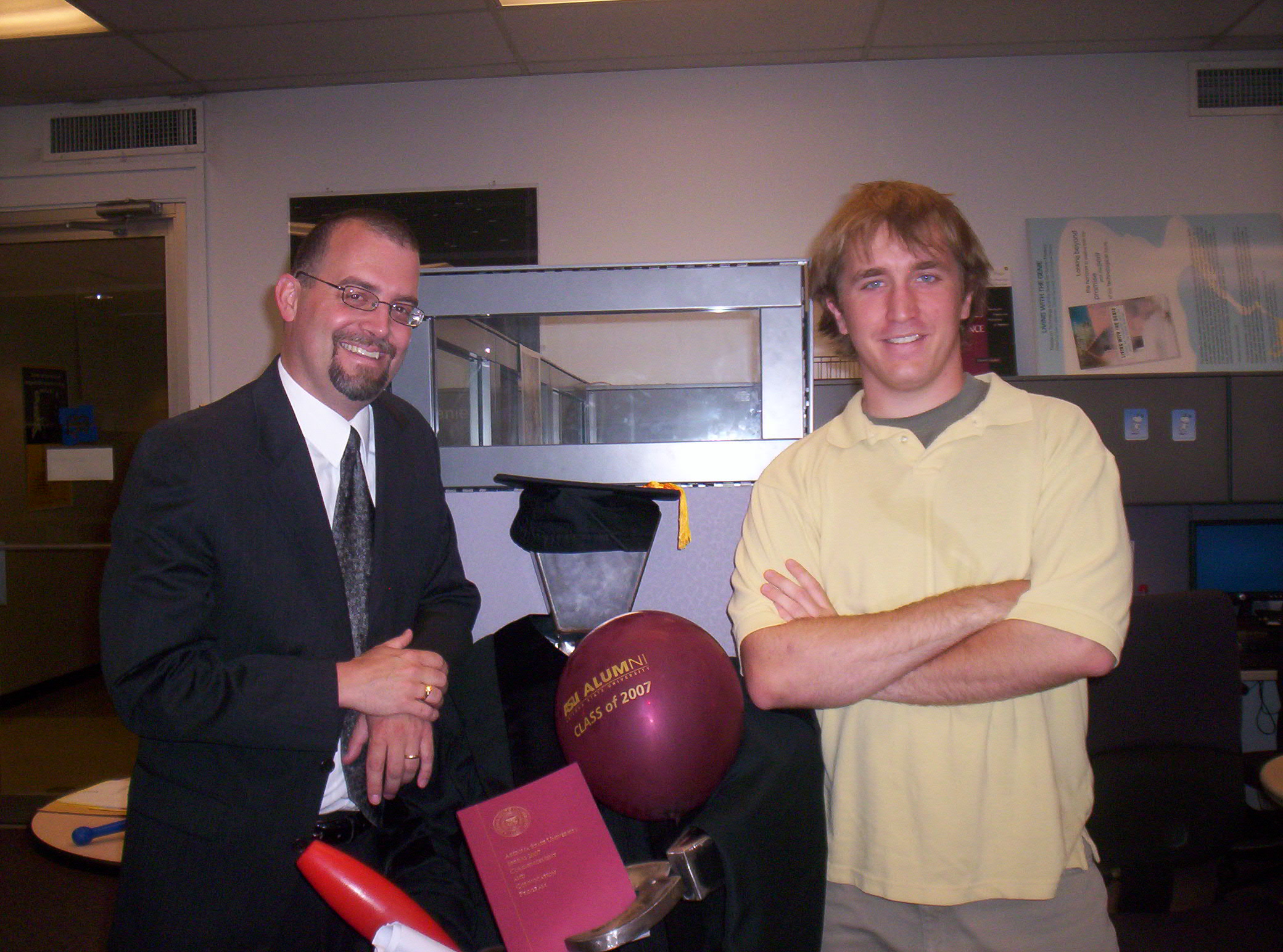

In 2007, Zachary Pirtle (right) celebrated earning undergraduate degrees at Arizona State University in both mechanical engineering and philosophy by Professor Clark Miller, today the associate director of the School for the Future of Innovation and Society. They are pictured in the campus office of the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes, where Pirtle served as an intern. Photographer: Lori Hidinger/ASU

He is currently a program executive and engineer for the Exploration Science Strategy and Integration Office, or ESSIO, in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.

He is among those in charge of Commercial Lunar Payload Services, or CLPS, deliveries to the surface of the Moon, with their first landing mission planned for later this year. He is also one of the key NASA leaders for the planned CLPS delivery of the VIPER rover to explore the Moon’s south pole in 2023.

Pirtle’s career at NASA has become a kind of family affair. His wife, Katelyn Kuhl, works in international relations for the agency. She recently negotiated agreements between NASA and the space agencies of Canada, Japan and Europe to jointly develop a space station to orbit the moon.

The couple recently welcomed their first child, daughter Gal Kuhl, into the world. Pirtle says her bedroom is already full of lunar and space exploration paraphernalia, along with children’s books about the philosopher Plato.

Philosophy and engineering collide

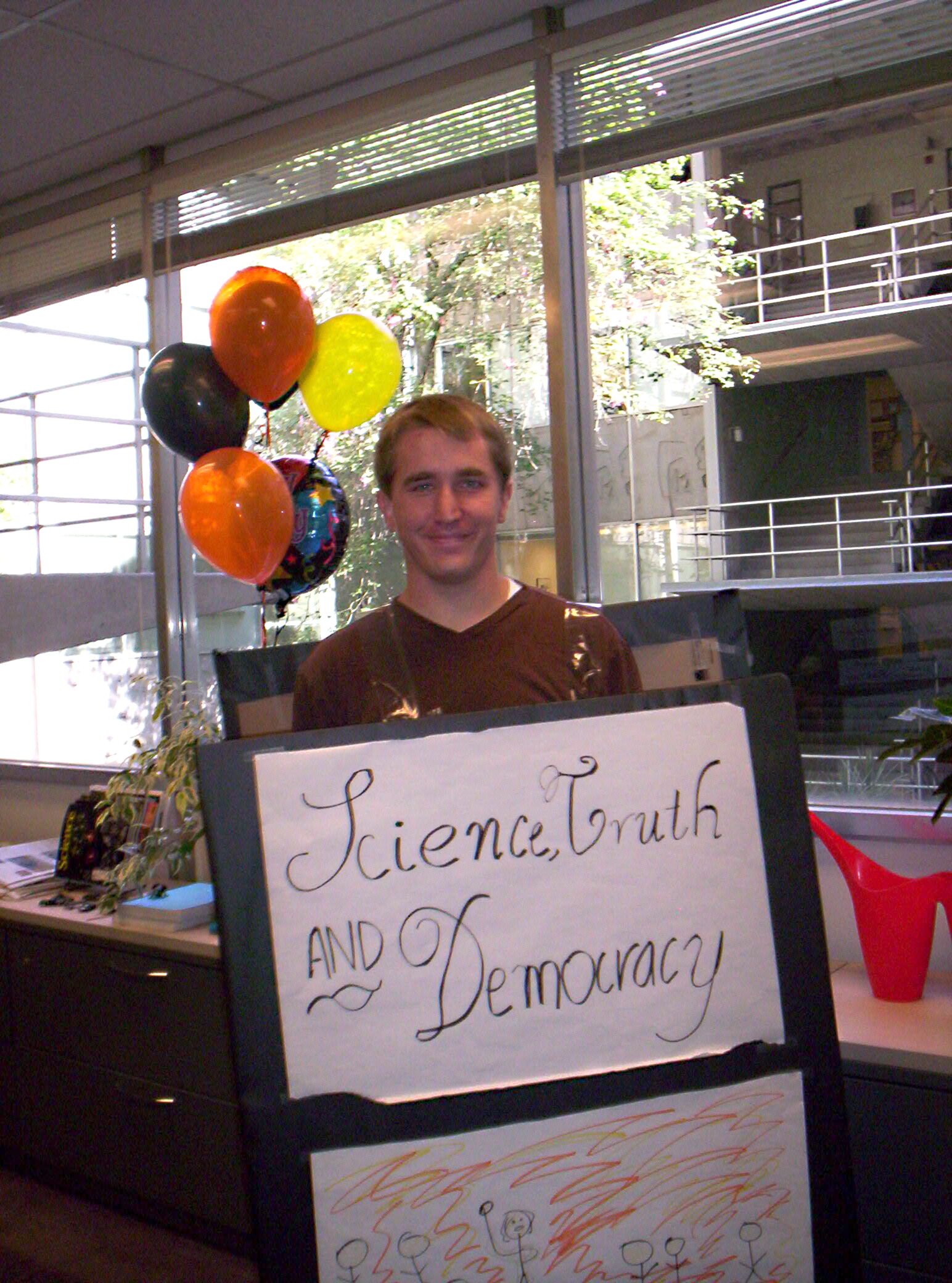

For his undergraduate philosophy thesis as a student in ASU’s Barrett, the Honors College, Zachary Pirtle focused on the philosopher Philip Kitcher’s book “Science, Truth and Democracy.” In 2006, Pirtle dressed up as the book cover for the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes Halloween costume contest and won the top prize. Pirtle has continued to publish in philosophy journals, primarily about issues in engineering ethics and epistemology, and has applied Kitcher’s thinking to his work on NASA’s goals for Mars exploration. Photographer: Lori Hidinger/ASU

Pirtle notes that during research for his undergraduate honors thesis, he was influenced by the book, “Science, Truth and Democracy,” by philosopher Philip Kitcher. He carried those varied but interconnected interests in science, engineering, philosophy and policy into his graduate work.

Pirtle’s academic and professional versatility provides a model for how today’s students could strive to elevate engineering’s stature as a robust source of innovation and creativity, says Fulton Schools Professor Brad Allenby,

Now, Pirtle says he is fortunate to be in a position to advocate for the values he developed through his academic endeavors.

“There are debates at NASA about what missions we should pursue and what our policies should be,” Pirtle says, “and given how science and engineering and technology shape society it’s a good thing that we take time to think about what we are choosing to do and how it will impact people.”

Professors praise Pirtle’s past, present and potential

Pirtle’s involvement in efforts to scrutinize the direction of the nation’s space program and the ramifications of its exploits doesn’t surprise Daniel Sarewitz, an ASU professor of science and society who co-founded and co-directs the Consortium for Science, Policy, and Outcomes, or CSPO.

“As a student at ASU, Zach was the kind of enthusiastic, endlessly inquisitive, intellectually adventurous student who keeps professors on their toes and helps makes classes more fun and engaging for everyone,” Sarewitz says. “Through the questions he asked and his gift for critical thought and interdisciplinary synthesis, Zach was really an intellectual partner from the beginning.”

He points out that when CSPO was in its early days, consisting of only a small number of faculty members, students and staff, Pirtle was a significant contributor to the culture and agenda of the group and its vision for improving the societal outcomes of science and technology advancements.

“I see him bringing this same spirit and vision to his work at NASA, where he is really having an impact,” says Sarewitz, who is based in Washington. D.C. “He’s helping to build a broader community of policy practitioners and academic scholars working on problems at the intersection of philosophy and technology. Having Zach as a colleague here in D.C over the years has been fantastic. I continue to learn from and be inspired by him.”

Richard Creath, a professor in ASU’s School of Life Sciences, remembers Pirtle as “curious, engaged, and skeptical, the ideal student” in the introductory philosophy of science course Creath taught. He recalls Pirtle moving on quickly to advanced courses designed primarily for graduate students.

“He thrived there, too. I was working out my conceptional engineering view of philosophy at the time, and Zach’s probing questions definitely improved my own work by forcing me to articulate it more clearly,” Creath says. “We have been encouraging and challenging each other ever since.”

Pirtle’s academic and professional versatility provides a model for how today’s students could strive to elevate engineering’s stature as a robust source of innovation and creativity, says Fulton Schools Professor Brad Allenby, who was one of Pirtle’s mentors and co-chair of his master’s thesis committee.

The increasing complexity of today’s world calls for engineers who are better able to comprehend and assess the economic, environmental, social, cultural and political aspects of the technologies and systems they produce and how those things will be used, Allenby says.

By taking his engineering education “beyond the technical into the philosophical,” Allenby considers Pirtle to have been at the forefront of an emerging trend for engineering students to branch out beyond the traditional disciplines related to their primary field.

Pirtle “has blazed a very different path,” both as a student and in his career, says Jameson Wetmore, an associate professor in ASU’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society, one of the faculty members who most influenced Pirtle. Wetmore now takes ASU doctoral students to Washington, D.C., to learn from Pirtle about how science policy is made.

Wetmore recalls being impressed that even as an undergraduate Pirtle worked to find ways to broaden the education of engineering undergraduates. Later, when Pirtle became “one of the few people with a technical background selected as a Presidential Management Fellow,” Wetmore says, “he worked with the organizers to recruit a much larger number of scientists and engineers into the program. Those efforts will impact others for years to come.”

In 2011, Zachary Pirtle (left) joined his 2010 NASA Presidential Management Fellowship cohort, Jesse Deihl, Matt Curtin and Kevin Gilligan, at the final launch of the Space Shuttle Atlantis, marking the end of that space shuttle program. As part of his job, Pirtle helped with the management and integration functions for the shuttle’s successor, the Space Launch System, which began in 2011. Photo courtesy of Zachary Pirtle