Haynes brings expertise in synthetic biology to ASU’s biomedical engineering program

Posted Feb. 21, 2012

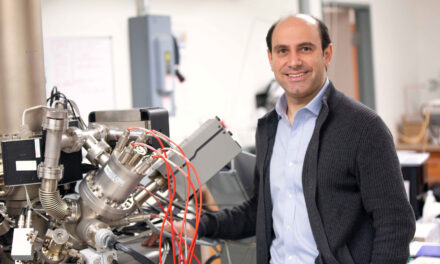

Karmella Haynes spent three years at Harvard helping make advances in synthetic biology before recently joining ASU’s faculty. Pictured with her in her ASU lab is biomedical engineering doctoral student Behzad Damadzadeh.Posted: February 21, 2012

Karmella Haynes jokes that she has opened up career opportunities for herself by being “a proactive, pragmatic bigmouth.”

Haynes, who joined Arizona State University last year as an assistant professor in the School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering, one of ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, was recently elected for a two-year term as a councilor for the Institute of Biological Engineering (IBE).

She’s now one of five councilors who serve as liaisons between IBE members nationwide and the organization’s executive committee. The position gives her a role in setting the agenda for the IBE’s annual conferences – gatherings that have an impact on shaping the course of education and research endeavors in the biological engineering field.

Haynes, whose area of expertise is synthetic biology, figures her outspoken nature is part of what brought her to the attention of the institute’s leaders.

She had written a blog commentary voicing objections to judging practices for the international Genetically Engineering Machine (iGEM) competition in synthetic biology for university undergraduate students.

“Instead of seeing [the blog post] as an affront, they viewed it as constructive criticism from someone who cares about IGEM,” she says.

Not long after her commentary, Haynes was offered a place on the 2011 IGEM judges committee, and she was able to help improve the judging rules for the competition.

While not timid in expressing her opinions, Haynes points out that her approach “is not only to complain but to follow up with what you want to see done, to offer a solution.”

She sees such earnest dialogue as important to the progress of synthetic biology, a growing and vibrant field but one that is still in the process of defining its goals, she says.

Haynes’s work focuses on combining natural materials to develop various kinds of engineered systems.

“Instead of using materials like plastic and metal, and other materials you would normally associate with engineering, we are using parts from nature,” she explains.

Among other things, she is working on “making a synthetic protein that has a predictable behavior in cells,” which can aid development of safer methods of injecting medicinal drugs into the body.

By engineering a protein to take the place of chemicals in the drug-delivery process, a specific amount of drugs can be more effectively delivered to specific locations in the body.

“The cool thing about proteins is that you can control what they do,” she says.

Synthetic biology also has promising applications in renewable fuel production and even in art (some living bacteria can be made to emit a neon-like luminescence in various colors that has been used for artistic purposes). “There is a lot of potential in the field,” Haynes says.

Her road into the field began as a high school student in St. Louis, where she developed a fascination for mathematical equations and puzzles. “It was like a fun language to me,” she says.

That fascination evolved into an interest in science and engineering when she discovered how mathematics could be applied to the quantitative side of biology.

She remembers her interest also being stoked by an unlikely source, the popular film “Jurassic Park,” with the plot revolving around the bioengineered re-creation of dinosaurs. “My dad was tickled that his 15-year-old daughter could point out the bloopers in the movie,” she recalls, referring to the inaccuracies of the science portrayed in the story.

Haynes was awarded scholarship to study biology at the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. Her undergraduate achievements there earned her a summer trip to Boston for an internship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that sparked an interest in genetics. It would then lead her to Washington University in St. Louis to earn a doctoral degree in molecular genetics.

She began turning toward synthetic biology in a post-doctoral research position at Davidson College in North Carolina, where her success earned her an opportunity to do more advanced work in the field as a researcher at Harvard University for nearly three years.

While there she helped develop a synthetic protein that is able to control gene expression and slow down the growth of cancer cells. She’s continuing that work at ASU.

“We want to create proteins that have an even stronger effect, that act only in certain types of cells, and that can be used to turn stem cells into useful tissues for regenerative therapy,” she says.

Haynes accepted the offer to join ASU because she saw the engineering program is “sincerely invested in advancing synthetic biology” and in having the subject taught in the hands-on fashion she prefers.

“I saw the potential to come in as a junior faculty member and be given an opportunity to make an impact and see my contributions taken seriously,” she says.

She was also attracted to an academic culture that encourages undergraduate students to work with faculty members.

“There are mechanisms in place to keep the students engaged with the professors. It’s an environment in which undergrads will volunteer, unsolicited, to assist with research,” Haynes says. “You don’t see things like this happening at many major universities.”

Two undergrads, in fact, helped Haynes start up work in her own research lab on campus.

For more on her team’s research, see The Haynes Lab website.

By Natalie Pierce and Joe Kullman