When online, we’re all too human

ASU cybersecurity doctoral student studies ways to protect users from themselves

Five people are listening…

This was the alarming message that Jennifer Grossman found on her computer screen one early morning about a year ago. The retired Arizona State University faculty member dialed the technical support phone number she found on the convincing-looking dialog box.

As Jennifer made the call, her husband Gary Grossman, an emeritus professor in the ASU School for the Future of Innovation in Society, awoke and listened in. The voice on the line claimed to be a specialist from Microsoft who told the couple that their computer had been hacked. They reacted in shock as the speaker read their credit card and bank account numbers aloud.

“It was very scary,” Jennifer Grossman says. “The person I spoke with used a lot of psychological techniques to keep me on the phone.”

The couple initially followed the instructions which included changing their usernames and passwords, but they balked when they were asked to transfer money from one of their bank accounts. On the advice of a bank teller, the Grossmans ended the interaction.

Known as a “tech support scam,” what happened to the Grossmans is part of a continuing rise in cybercrime. A recent report says that victims lost more than $1 trillion globally to scammers in 2024.

“This cybercrime technology is developing more quickly than our efforts to effectively respond,” Gary Grossman says.

But researchers in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at ASU, are hoping to change that.

Ananta Soneji is a cybersecurity doctoral student in the Fulton Schools. Working under the supervision of Adam Doupé, an associate professor of computer science and engineering, she specializes in human factors security research and is part of a team of students and faculty members working hard to design new technology that protects users from computer scams and cyberattacks.

The insider threat

As part of efforts to make ASU a global cybersecurity hub, Soneji studies the role that people play in the realm of digital security and how to best consider their needs when designing new systems. By investigating a broad range of security topics, including cybersecurity in enterprise, educational technology and hacker communities, Soneji hopes to create a safer online world.

After receiving her master’s degree in computer science from the Fulton Schools, Soneji contemplated what to do next. Inspired by her father who holds a doctoral degree in civil engineering, she joined the doctoral program in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence.

“At that point, I knew I wanted to pursue cybersecurity research, but I related more to the human side of it,” Soneji says. “I wanted to explore how to connect sociology and psychology and see how these impact cybersecurity systems.”

Historically, cybersecurity has focused on the development of defensive features such as antivirus software and digital firewalls. The modern computer security era began in 1972 with Ray Tomlinson’s creation of Reaper — the first example of antivirus software which was designed to delete Creeper, the world’s first computer worm. In this paradigm, hackers write code that attacks systems, and computer engineers create software that defends them.

But today, data breaches, often triggered by simple, innocuous mistakes by authorized users, create the most significant vulnerabilities. According to a Verizon study, 68% of security problems begin with a person falling victim to a social engineering attack such as the tech support scam experienced by the Grossmans, or with an employee making an error.

For this reason, the work being done by researchers like Soneji is gaining importance. She has participated in a variety of projects, studying ways to ensure privacy and protection for students who use educational software and how to extract useful lessons from hacker behavior.

To do her work, Soneji has developed expertise in qualitative analysis, a methodology in which researchers use non-numerical data, such as interviews, to identify trends and themes. Using this information, she and her colleagues hope to gain keen insights into user behavior and design future systems with human-centered insights in mind.

Soneji’s research papers have been accepted for publication by numerous top professional conferences, and she has served as a mentor for high school and undergraduate students.

In 2024, Soneji assisted a team in a groundbreaking study on the protection of online content creators.The project, led by Elissa M. Redmiles, an assistant professor at Georgetown University, studied vulnerable online groups and made recommendations on how to protect their security and privacy.

Redmiles says Soneji was a valued member of the research team.

“Ananta efficiently and collaboratively analyzed data and reported on that analysis leading to a paper published at a top security venue that contributed to the existing body of knowledge, including an evaluation of an established framework on the safety of at-risk users,” Redmiles says.

Putting people first

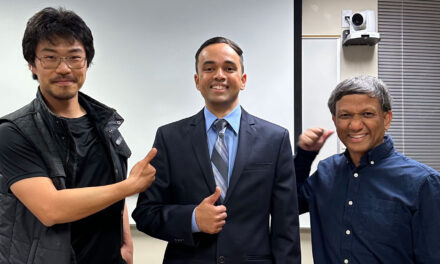

It was while considering Fulton Schools doctoral programs that Soneji connected with Doupé.

“I think he said something along the lines of, ‘Oh good, another people person,’” Soneji says with a laugh.

Doupé, a leading cybersecurity expert, encouraged Soneji to join the Laboratory of Security Engineering for Future Computing, a research center he co-directs. The group seeks to consistently advance cybersecurity technology and play an active role in curbing cybercrime.

“Ananta is the best kind of scientist: curious yet skeptical, creative yet detail oriented. She works very hard to conduct novel research and expand the bounds of what we know about the intersection of humans and security,” Doupé says. “I’m confident that she will be a leader in the area of usable security.”

In the future, Soneji wants to provide the same type of inspiration that Doupé has given her to the next generation of cybersecurity students that Doupé has given her.

“Dr. Doupé always brings a unique angle or perspective to a research discussion. And sometimes that new direction is beautiful to explore,” she says.

Soneji adds, “In five years, I see myself as a university professor guiding students in cutting-edge research on human factors, user privacy and cybersecurity systems, contributing to a safer digital world for both vulnerable and mainstream users.”

Jennifer Grossman is hopeful that work like Soneji’s will be better able to protect people in the future with solutions that might flag suspicious alert messages or provide clearer access to legitimate support. The Grossmans continue to grapple with the aftereffects of the hack.

“It was a huge burden to change all our credit card, bank account and phone numbers,” she says. “On one hand, we were embarrassed, but on the other, the team who targeted us was very good.”