ASU 3D printing lab creates opportunity for plastic recycling

It’s 27 hours and 14 minutes into a 40-hour 3D print job, when the 3D printer hiccups and takes over your masterpiece/prototype/capstone project piece/replacement part that will save you $10,000. The next 12 hours and 46 minutes worth of the print job ends up as a frizzy nest of plastic spaghetti. It’s a total loss. Toss it.

Or, if you’re working in Arizona State University’s 3D Print and Laser Cutting Lab on the Tempe campus, you can recycle it.

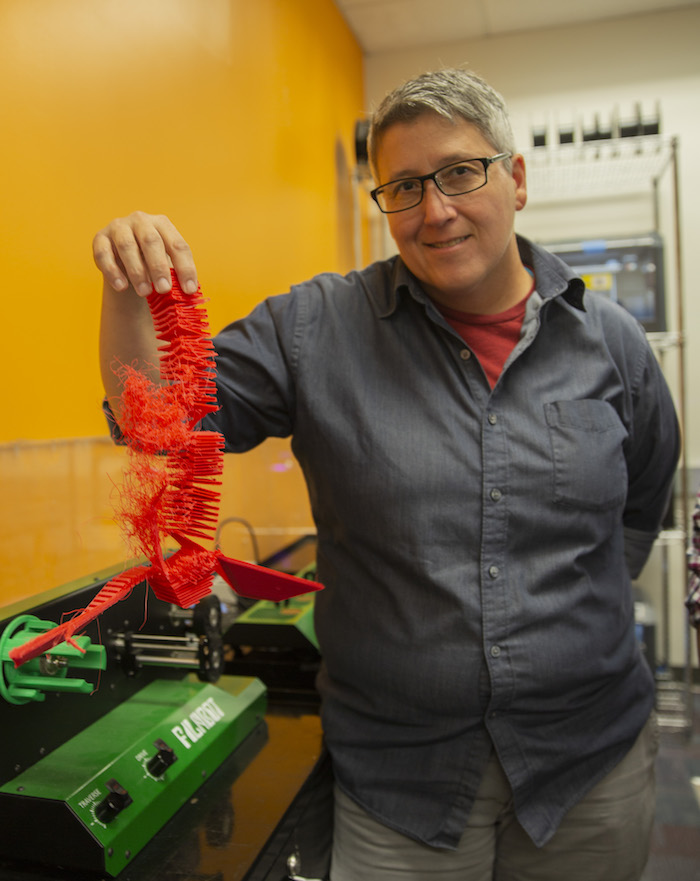

Myrna Martinez, an academic facilities specialist in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, holds a piece of waste PLA plastic in the 3D Print and Laser Cutting Lab. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

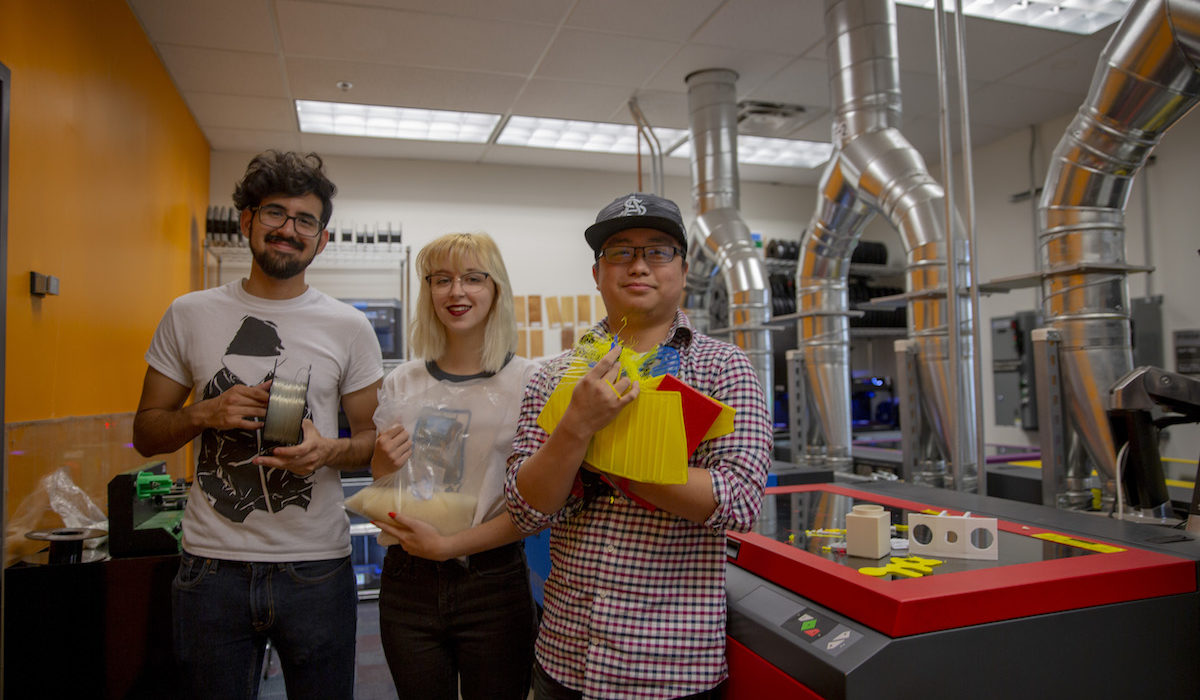

The 3D Print and Laser Cutting Lab was established about three years ago to help more than 500 students each semester in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering introductory course FSE 100 develop their first engineering projects with 3D printing.

Other students also use the lab to 3D print and laser cut prototypes for entrepreneurial projects, pieces for student organization competitions and components for capstone projects. Faculty can also request prints for models and parts, and the lab is also available for staff to use.

Myrna Martinez, an academic facilities specialist, runs this lab with help from Fulton Schools students like Kenny Truong, a mechanical engineering sophomore, and Ruy Garciaacosta, a mechanical engineering senior.

As more students and faculty at ASU use the lab, more plastic could have potentially ended up in the trash, but YouTube provided a solution.

3D printing life cycle 101

Mistakes and extra “waste” plastic are all part of a 3D printer enthusiast’s life. Breakaway parts called rafts and other stabilizing support structures are necessary for many designs — “because physics,” Truong says. Additionally, designs may not turn out as expected or end up being structurally unsound.

However, with the right tools these failed, subpar and extra pieces are all recyclable.

Most consumer 3D printers use a type of plastic called polylactic acid, polylactide or PLA. Printers use spools of PLA thread called filament to print a 3D structure layer by layer in a single, continuous line of plastic.

PLA is a biodegradable plastic created from renewable sources such as corn starch or sugarcane. While much friendlier to the environment than petroleum-based plastics — like high-density polyethylene used to make the grocery bags sea turtles mistake for jellyfish — referring to PLA as “biodegradable” is a bit misleading. PLA still takes hundreds of years to biodegrade in a typical landfill.

But PLA is recyclable in a way that’s similar to “recycling” crayon stubs. The general principle is the same: cut up the pieces into small pellets, heat them up, mold the now-pliable, hot material into the desired shape and cool it down.

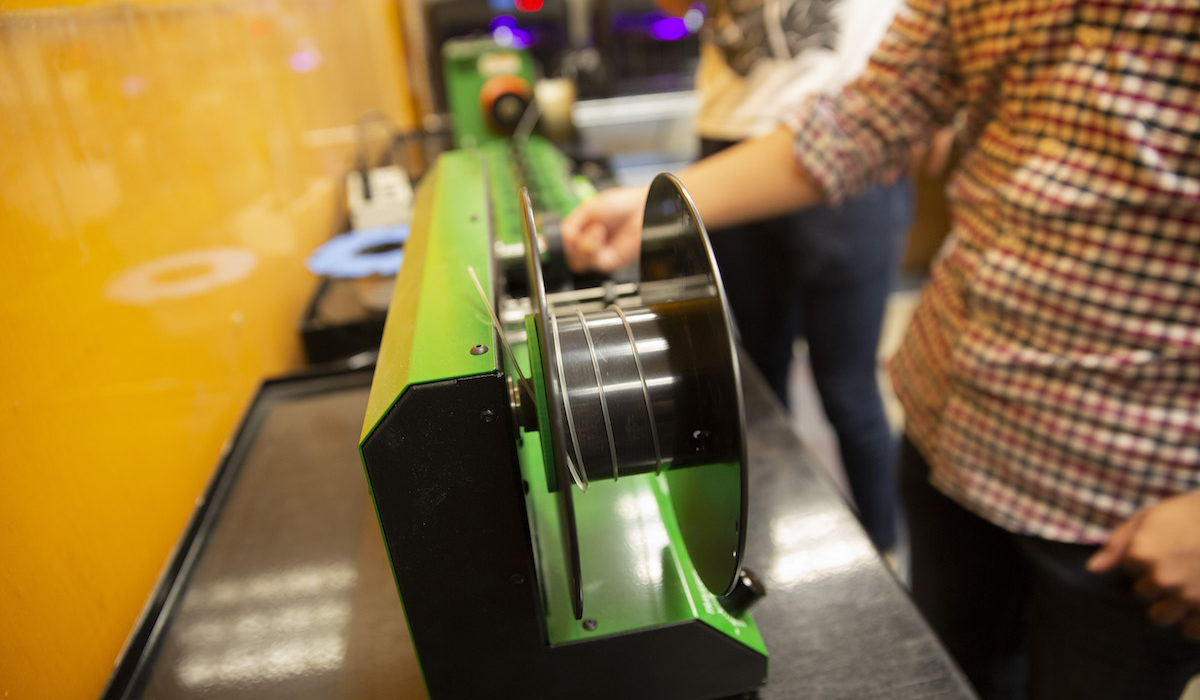

Subpar prints, structural support pieces and printer failures can all cause waste PLA plastic when 3D printing. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

For PLA 3D printer filament, this involves a reclaimer that acts like a woodchipper, an extruder that heats up the pellets and pushes the heated plastic through a tube like a spaghetti maker then runs the material along a fan to cool it, and spools it on a regular 3D printer filament spool.

Martinez and Matthew McWhorter, who is also a Fulton Schools academic facilities specialist, saw an open source Filabot extruder system on YouTube a couple years ago and thought it would be an excellent addition to the lab.

With enthusiastic support from ASU Zero Waste and Fulton Schools Vice Dean for Academic and Student Affairs James Collofello, who directs the lab, Martinez and McWhorter got approval to use the system in the lab and got to work building the extruder in January. Because it was all plug-and-play, setup was a breeze and all the students had to do was design and print an adapter for the winding tool to use their existing spools.

Sounds easy, but the recycled plastic must be extruded in a precise way to get a uniform thickness required to prevent jamming a 3D printer nozzle. It took Truong and others on the lab team about seven hours of testing over the summer to get their filament right.

So far, they’ve created two spools of recycled material, averaging two days to create one spool of filament at uniform thickness. They’ve created a few test prints with their recycled material, including a USB drive holder.

“It was super cool to use the material for the first time,” Truong says. “We made it ourselves and we’re turning what would just be thrown away into another useful project for a student.”

The filament extruder system — dubbed “Bob Ross” because “it takes our filament mistakes and makes them into happy little 3D-printed trees,” Garciaacosta says — helps students involved in the lab develop sustainable habits and consider the environment in their work.

Closing the loop

When Martinez and McWhorter first proposed the idea of an extruder system in their lab, ASU’s Zero Waste Associate Director Alana Levine was immediately on board.

The system plays into the bigger trends of recycling, sustainability and circularity at ASU and beyond.

People and businessesare becoming more aware of the need to reduce their use of single-use plastics. Starbucks, American Airlines and other major companies, for instance, recently stopped using plastic straws.

Global economic policies have also made local recycling solutions more important.

“China, for example, has really cracked down and created a lot of policy to not take a lot of waste material,” Levine says. “It’s paramount to find downstream solutions for these types of materials we’re generating as waste.”

A USB drive holder made out of recycled PLA plastic created in the 3D Print and Laser Cutting Lab. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

Levine emphasizes the importance of circularity, or putting these waste materials back into the marketplace as another useful material or item.

In practice, this circularity loop can be at the global scale, but the smaller the loop the less impact there is on using additional resources to ship materials and recycled products.

“Ideally it would be great if we can have local reprocessing for our waste materials,” Levine says.

The extruding tool at the 3D Print and Laser Cutting Lab is an example of local reprocessing.

“I love that there was an opportunity to demonstrate a fairly complex process of waste material production, collection, reprocessing and getting that product back into a stage where it can then be useful again, where we’re directly recycling and not downcycling the plastic or making it less valuable,” Levine says.

Future steps

PLA can’t be recycled infinitely. Martinez notes other labs that use similar recycling systems recommend only recycling the same material a couple of times. So she and the students find other ways to reduce waste.

However, not everything that’s printed will be thrown away and it isn’t an immediate concern for the team.

Garciaacosta also says the students who help manage the lab also try to find optimal ways to design each print to minimize material usage and other factors. The goal is to design smarter, not harder.

“I sometimes suggest people use a combination of 3D printing and laser cutting wood, for example making their base out of wood and 3D printing the joints for a job that uses much less plastic and is faster to produce,” Garciaacosta says. “It makes people think how they can optimize designs and make them more environmentally friendly because they’re using less material.”

Martinez is also working with other campus labs with 3D printers to collect their waste PLA material. She’s also contacting labs that produce plastic waste compatible with recycling into 3D printer filament. For example, syringe caps from biomedical engineering labs can be recycled using the extruder tool.

Levine is also helping to reach out to corporations and companies outside of ASU to provide their waste materials to ASU recycling programs like this one.

“The ultimate goal is to collect so much recycled material that it would be too much for us to handle to reuse here as finished spools,” Martinez says. “We talked about donating recycled PLA to K-12 STEM programs that have 3D printers at their schools to reduce their expenses.”

Martinez believes this is a good practice for her students to take with them to industry.

“The idea is to incorporate recycled plastic and other materials into their existing engineering builds,” she says. “It helps them create good habits and consider the environment.”