New fellowship brings inclusivity to language analytics

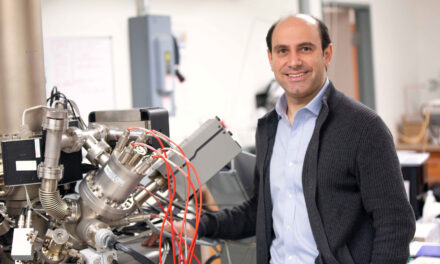

Above: Human systems engineering Associate Professor Rod Roscoe provides direction to a student learning how computer-based tools can support effective learning processes at the Sustainable Learning and Adaptive Technology for Education Lab, or SLATE Lab, located within The Polytechnic School, one of the six Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University. Photographer: Jessica Hochreiter/ASU

We all have our biases. But few of us consider how biases can inadvertently shape the design and execution of research.

For example, testing mobile device ergonomics among mainly male participants could result in smartphones that are too large for many female hands. Or testing the safety of autonomous vehicle optical systems with only lighter-skinned pedestrians in well-lit environments may not protect darker-skinned individuals walking at night.

Understanding the effects of cultural biases in a research setting has become a topic of interest among scientists in various fields. They ask, how does unintentionally excluding certain demographic groups from a study skew its results in a non-inclusive way? And how might this perpetuate inequitable social conditions?

Human systems engineering Associate Professor Rod Roscoe at The Polytechnic School, one of the six Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University, is partnering with the Learning Agency Lab also known as the Lab, to expand understanding of the biases that exist specifically in language analytics research. Together, they have launched a fellowship program funded by a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation award focusing on promoting inclusion and equity within research in this field.

“Language analytics is a fusion of fields like data science and linguistics, often using computer-based tools to detect features of natural language and then relying on that information to guide assessments, make decisions and advance human-computer interaction,” Roscoe says. “Examples of these applications are everywhere — automated tools for closed captioning or dictation, voice-activated controls and software that gives feedback on writing style or grammar.”

These applications function by using artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to link key language components to valuable outcomes, like making cohesive text or understanding a spoken command.

Inherently, algorithm formation depends heavily on the data source — in this case, the language that defines what the algorithm measures. Ideally, these algorithms should work with a healthy variety of language from people of different backgrounds and cultures, such as those who speak English as a second language or who speak with different dialects. This diversity allows the algorithms to capture and respond to an authentic range of how real people use language.

Roscoe and his colleagues believe that many current natural language processing tools and applications are not being developed in this way and are therefore contributing to inequity and exclusion in language-based technologies. He proposes the question, “Who decides what counts as good writing and communication?”

“The people whose text is being used to develop language tools are most likely from a narrow demographic that doesn’t represent the general population or important subgroups,” Roscoe says. “If we aren’t careful, cultural and gender biases can be built into the algorithms that support these products. And once they are built into the algorithm, it becomes difficult to undo. They become part of the ‘black box’ of the software and taken for granted.”

Linguistic biases narrow the range of language that is considered correct or permissible, and they penalize users who aren’t using language according to those standards. For instance, restrictive beliefs about “proper English” or “professional English” might lead to devaluing ideas from those who are nonnative English speakers or have not been taught to write or speak in a certain way.

“We are recreating our prejudices by putting them into a computer,” says Roscoe who will serve as the lead investigator on this project.

The collaborative goal of the Inclusive Language Analytics Fellowship Program is to advance both the research and the researchers in these fields. Roscoe and the Lab aim to recruit two recent doctoral graduates from underrepresented backgrounds as fellows to investigate inclusive language analytics and to be mentored by diverse learning engineering and language experts at ASU and from other institutions across the country.

Fellows will be encouraged and expected to participate in career and equity development opportunities, attend workshops on grant and resume writing and attend training programs that discuss racism, sexism and other societal issues.

At ASU, fellows will be invited to participate in events and dialogues sponsored by organizations such as the ASU Postdoctoral Affairs Office, the Committee for Campus Inclusion, the Center for Gender Equity in Science and Technology, the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy, Project Humanities and others.

The idea for this fellowship was developed alongside another project at the Lab to improve the algorithms that drive assisted writing feedback tools. In partnership with Georgia State University, the Lab has collected a robust dataset of student responses that will be available to fellows for research.

The Lab will help manage the project by ensuring the fellows stay on track and share their findings in academic and public audience venues, and by finding speaker opportunities. A large network of professors with different specializations from various institutions will assist in providing research advice and career opportunities in addition to mentorship for the fellows.

“We want to provide layers and layers of support so the fellows feel validated in their research,” says Aigner Picou, program director at the Lab. “The best outcome would be that the fellows are placed at institutions in full-time positions sharing and implementing the knowledge they’ve learned at this fellowship.”

“If we are not thinking of diversity and equity as we build technologies, people will be excluded, or worse, punished or harmed based on the biases we build into the software,” Roscoe says. “Inclusive language analytics is about making sure that doesn’t happen or continue to happen.”