Jennifer Blain Christen stimulates nerves and young minds

Above: Jennifer Blain Christen is entering an entirely new field of medicine — electroceutical. This field treats diseases with the direct electrical stimulation of specific nerves, triggering self-treatment within the body, generally with the use of electrodes. Photographer: Pete Zrioka/ASU

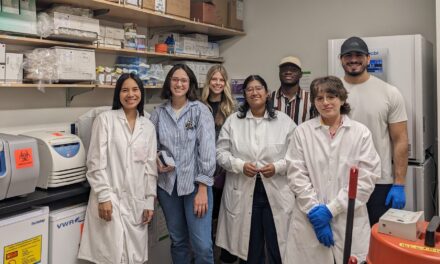

Along with using her engineering expertise to develop cutting-edge diagnostic tools for use in health care, Jennifer Blain Christen is also venturing into new forms of treatment. Moreover, the associate professor of electrical engineering is entering an entirely new field of medicine — electroceuticals.

“This emerging field aims to electrically stimulate the nervous system to eliminate or reduce the need for pharmaceuticals,” explains Blain Christen, a faculty member in Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

This approach treats diseases with the direct electrical stimulation of specific nerves, triggering self-treatment within the body, generally with the use of electrodes.

This method has drawbacks; one being it’s a broader form of treatment affecting more than just the targeted nerve, which presents unwanted side effects, notes Blain Christen. In addition, electrode stimulation is also invasive, cutting into the nerve to stimulate it.

To overcome this limitation, her project opts for a different method to stimulate nerves: light. Light can stimulate a nerve without cutting into and damaging it, and is more accurate than other stimulation techniques.

“The reason this is exciting is because you can target specific nerves, opposed to an entire bundle,” says Blain Christen.

Blain Christen has discovered she can target specific nerves with the use of flexible display technology, commonly found in flat-panel televisions. By wrapping a miniature flexible display around a nerve, she can beam light from numerous pixels to intersect at one point, generating enough light to stimulate a response.

She’s currently experimenting with motor neurons, as those provide a direct, visible form of feedback in the form of movement, through a traditional, electrode-based approach.

“We’re looking for a downstream response from the motor neurons — basically, we’re looking to see that when we tell the nerves to turn on, they do just that,” says Blain Christen.

Our nerves’ jobs are to take a signal from the brain and activate a muscle, explains Blain Christen, so they’re gathering data using a more traditional approach — an implanted electrode — which they can then use to measure the amount of light to input for stimulus later down the line.

Her work is supported by a five-year, $500,000 National Science Foundation CAREER award, which recognizes emerging education and research leaders in engineering and science. The funds also support Blain Christen’s development of a bioelectronics workshop aimed at introducing middle school students to the world of bioelectronics and how they are used in therapeutic and prosthetic technology.

So far, Blain Christen has visited about a half dozen middle schools, bringing fun activities to engage young minds in science. One activity involves running a song’s electrical current through a detached cockroach leg. The insects’ legs — which are naturally shed as a survival mechanism against predators and regenerated, much like a lizard’s tail — pulse in time with the music. The dancing motion, while a little gross, is an excellent illustration of bioelectrics and neural interfaces, says Blain Christen.

In addition to making bug legs dance, she utilizes electromyography, or EMG, to show students how electrical signals are important to your body and how they affect the different organs and systems within the body. The activity allows students to place EMG stickers on their arms to stimulate motor neurons or make an audio recording of the signal.

“I think it’s really important that we do this kind of stuff because kids need to like science, especially if they’re female, before they think that they can’t do it,” says Blain Christen.

Blain Christen’s drive to expose young minds to science early goes beyond simply receiving funding to do so. Growing up in a small town in Illinois, she says there were not many opportunities to become involved in scientific disciplines outside of agricultural science.

“There was an FFA — Future Farmers of America — and it was the club to be in,” she recalls.

That all changed when she decided to attend Illinois Math and Science Academy her sophomore year, which accelerated her education so much that she didn’t require any math credits to attain her engineering degree years later.

“There was no way I would have ended up at Johns Hopkins if I had stayed in the school I was in,” she says. “I think about what my life would have been like had I not had these opportunities, so I want to see that other people have similar ones. So as much as I can, I want to give back because I had a great opportunity like that.”