Will nature-inspired soft robots spark the next tech revolution?

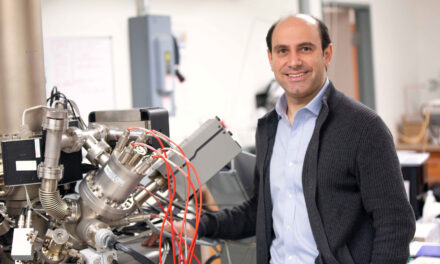

Above: Harvard University Professor George M. Whitesides and Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering Dean Kyle Squires pose at the April 4 Dean’s Distinguished Lecture at ASU. Whitesides, a pioneer in the field of soft robotics, spoke to faculty and students about how he has created simple, nature-inspired robotic designs made of soft, elastic-like materials. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

Imagine a basic, primitive life form on a sandy beach. Its primary survival tactic is to get out of the way of potential predators. What is the simplest way it could move?

At the 2018 Dean’s Distinguished Lecture at Arizona State University on April 4, George M. Whitesides posed this problem to demonstrate how biomimetics, or imitating nature in movement and materials, can create “life that never was” — soft robots.

Whitesides, a professor of chemistry at Harvard University and pioneer in the soft robotics field, shared how he has created new and simple models of life forms out of a natural material response to pressure that no one had found interesting before: buckling.

When metal buckles, such as when a car’s frame is smashed, the result is often irreversible and renders the structure useless. However, a buckling action in soft, stretchy materials, such as rubber, is reversible. The ability to buckle and unbuckle repeatedly allows for dynamic movements that can be useful for a wide variety of robotic tasks.

“Where you bend the material, it’ll buckle. It remembers the stresses you put into it. It’s an interesting way to do programming in an analog way,” Whitesides says.

Whitesides uses air pressure and vacuums, or pneumatics, to buckle stretchy materials called elastomer polymers to create robotic systems that move or grab.

George M. Whitesides spoke about soft robotics to a full auditorium at Arizona State University’s Tempe campus on April 4. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

The lack of onboard complex, sophisticated computers or electric systems used for movement give these soft pneumatic systems added advantages. They’re less likely to break and better able to withstand conditions unsuitable for electronics, such as underwater or high-radiation environments.

This simplicity is also key to the potential that soft robotics offer for entrepreneurship, says Whitesides, who holds more than 50 patents and has started more than 12 companies.

One of the companies Whitesides created is based on the concept of a soft, starfish-like, inflatable robotic gripper. [Watch a video of an early example of this concept from Whitesides’ lab.]

“[The company] worked only because we’ve stripped out all the computers and controllers and made it about as simple as you can make it with material science,” Whitesides says.

Besides simplicity, the concept also needs to be something people care about — in other words, it has to have a market. And many industries care about the capabilities and possibilities of soft robotics. The grabbing and movement abilities of soft robotics designs can be applied to food production, e-commerce, biomedicine, heavy industry and hazardous jobs.

[Read about how Fulton Schools soft robotics researchers could help Arizona utility company Salt River Project clear waterways.]

Though Whitesides has been a major player in getting the field off to a running — or at least a primitive walking — start, there is a long way left to go from developing new soft robotics designs in the lab to putting them to work in the real world. At the ASU lecture, Whitesides tasked a packed room filled with the next generation of engineers and scientists at ASU to help continue his work in soft robotics.

The lecture was part of the Dean’s Distinguished Lectures series the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering have conducted since about 2013.

Ram Pendyala, a professor of civil and environmental engineering in the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, leads the Fulton Schools Executive Committee tasked with identifying prominent individuals to speak on a variety of science and engineering topics at the annual Dean’s Distinguished Lecture.

“The Dean’s Distinguished Lecture is intended to bring accomplished scholars and pre-eminent leaders in engineering and the sciences to our enterprise so that faculty and students get to interact with a leading scholar of great repute and engage in a dialogue about a wide range of topics,” Pendyala says.

Kyle Squires, dean of ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering and professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering, says Whitesides’ talk was an opportunity to explore an engineering topic, provoke thoughtful discussion and challenge how the Fulton Schools community approaches the work they do each day.

“It was an honor to host Dr. Whitesides, a prolific scholar whose scientific contributions and insightful perspectives can inspire engineers at every stage of their careers,” Squires says.

Assistant Professor Barbara Smith, introduces George M. Whitesides, who was her postdoctoral mentor at Harvard University. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

At the lecture, Squires noted that Fulton Schools faculty often have connections to the high-profile scholars invited to speak at the lecture series.

“Many of our great faculty have come from great places themselves, and those connections have led to an invitation for what I’m sure will be a very powerful lecture,” Squires says.

One of those connections is between Whitesides and Barbara Smith, a former member of Whitesides’ lab at Harvard University and an assistant professor of biomedical engineering in the Fulton Schools.

Many of the more than 200 attendees were Fulton Schools students and faculty who work on robotics and related engineering research.

Smith, who introduced Whitesides at the lecture, said that Whitesides started many fields of engineering and “if you have it in your lab today, it likely links back to Professor Whitesides’ lab.”

Smith says it was motivating to have her postdoctoral mentor, Professor Whitesides, speak to students across the Fulton Schools.

“He has a deep well of knowledge in and around a multitude of different scientific areas,” Smith says. “His inspirational talk may have shown the students new and exciting possibilities that will shape their way forward in research and entrepreneurship.”