ASU engineering alum inspiring student response to COVID-19

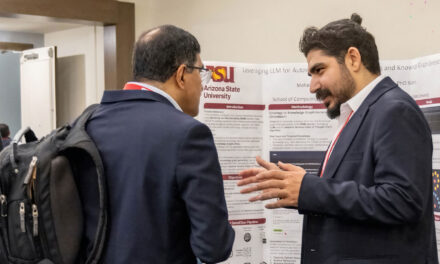

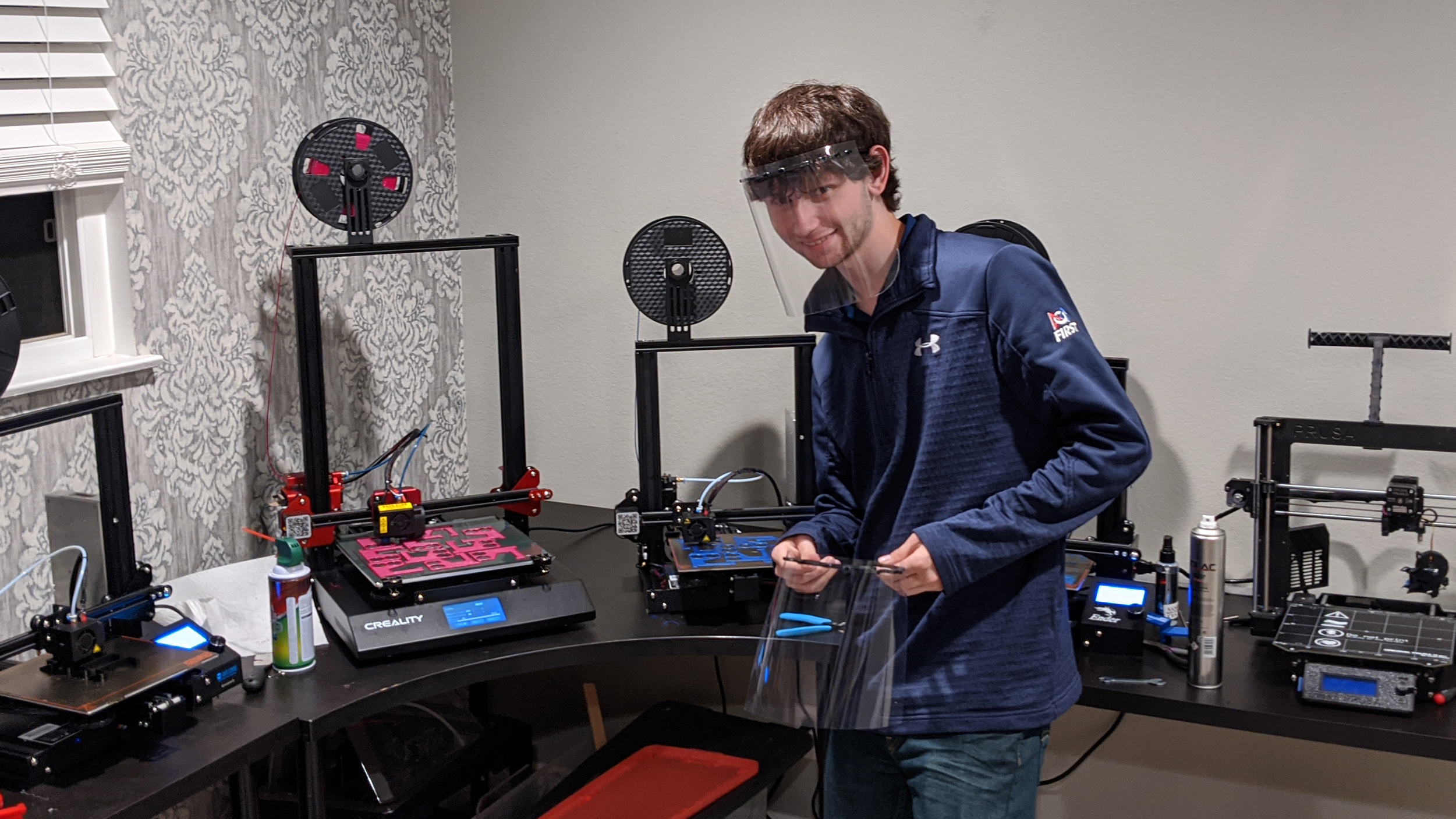

Above: Aaron Dolgin applies project management skills that he learned as an engineering student at Arizona State University to coordinate a network of student maker groups producing medical face shields in response to the novel coronavirus pandemic. Photo courtesy of Aaron Dolgin

Aaron Dolgin is a systems engineer for Northrop Grumman in Los Angeles. He started work with the aerospace and defense technology giant after graduating from Arizona State University in 2018 with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering.

While a student in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at ASU, Dolgin completed two summer internships with the company. Those experiences revealed a broad range of career opportunities, and his process of discovery continues as an employee.

“I’m involved in a rotation program,” he says. “It allows me to move within the organization every year for three years in order to try different positions and determine what I like to do best.”

Alongside his professional work, Dolgin mentors three student robotics competition teams in southern California. One of them is Project 691 at West Ranch High School in Santa Clarita, where he was a student.

“I really enjoyed the robotics program in high school, so I wanted to make sure I gave back in some way,” he says. “During college at ASU, I volunteered at robotics events in Arizona, and I knew I wanted to continue that kind of support when I came back to California.”

With the advent of COVID-19, Dolgin’s efforts in this volunteer community have expanded dramatically. He now co-leads a network of more than 150 people who are donating time and talent to supply medical face shields to approximately 125 health care facilities across California and 10 other states.

The SoCal Makers COVID-19 Response Team formed only eight weeks ago, but it already has manufactured, assembled and distributed more than 15,000 pieces of personal protective equipment, or PPE.

Recognizing opportunity to engineer solutions

Dolgin says the effort began with Eric Gever, a friend who works as a systems engineer for Boeing and also mentors robotics team students in southern California. As the need for medical PPE suddenly surged, Gever and Dolgin saw an opportunity to engage their professional and personal networks to provide vital community service.

Output is relatively simple. Face shields are 3D-printed visor frames with thin transparency sheets attached. Designs and specifications are available from a National Institutes of Health website. Equipment and expertise come courtesy of some engineering peers, but mainly from enthusiastic student makers.

“Many high school and college students have personal 3D printers at home. And some schools have allowed their students to take printers home,” Dolgin says. “We also have volunteers who are helping with logistics, picking up finished parts and delivering them to Eric’s home or to mine. Our two places have become distribution centers.”

Initially, it all happened by word of mouth or through messages on social media. But the accelerating influx of both volunteers and mask requests soon presented a challenge.

“We suddenly had to onboard all of these people, standardize our production processes and fulfill orders from a lot of health care facilities,” Dolgin says. “It came down to effective project management.”

Maker groups, which apply digital technology to design and create a variety of objects, function in different ways. Among high school teams supporting the SoCal Makers effort, it may be teachers or mentors who print all of the material while the students assemble the face shields and complete post-processing work to verify quality. College students often bring a broader suite of skills, especially those using this collective effort as part of their senior-year capstone projects.

Since all of the labor is volunteer, Dolgin says the SoCal Makers leadership is sensitive to burnout. Every two weeks they ask participants whether they will continue to be available and whether their production capacity is changing.

“We need to anticipate any significant variations,” he says. “In early May, our output dropped because students needed time to prepare for finals. That means we had to extend lead times in our schedules so we could still deliver what we promised and when.”

Some materials necessary to produce PPE are purchased using donations to the team’s GoFundMe account. Other resources are repurposed supplies that might otherwise be destined for a landfill.

“For example, most school districts don’t use overhead projectors anymore. Classes operate with document cameras and smart boards,” Dolgin says. “Even so, there are districts with boxes of transparency sheets just sitting in storage rooms and warehouses. We can certainly use them for this cause.”

As SoCal Makers continue to produce PPE for health care staff battling the pandemic, Dolgin says more support is welcome.

“Volunteers don’t need any prior technical knowledge. Some people have even purchased 3D printers just so they can join the effort,” he says. “They may struggle a little at first, but we have a remarkable community ready to get everyone up to speed. All of us are figuring things out together.”

Dolgin says that learning to work effectively within a group and across multiple groups was an important aspect of his time at The Polytechnic School, one of the six Fulton Schools. That skill has proven enormously valuable to his professional life and now to his volunteer work.

“The project team model I learned exactly parallels what I do now,” he says. “As an engineer, you are never called on to know everything about a given aircraft or satellite — or PPE. But you do need to know how to connect with the right people to find the information you need, and then apply it with your colleagues to solve problems.” He adds, “Engineers are not known for having the best people skills, but developing those very skills at ASU is something that I have really appreciated.”