Seeking the biometric bill of rights

ASU cybersecurity expert warns that our most personal data must be better protected

This article has been updated to reflect new developments

Katina Michael warns that your DNA data may not be as safe as you think. In some cases, consumer genetic testing companies, such as those that specialize in decoding ancestry, are not bound by federal medical privacy laws.

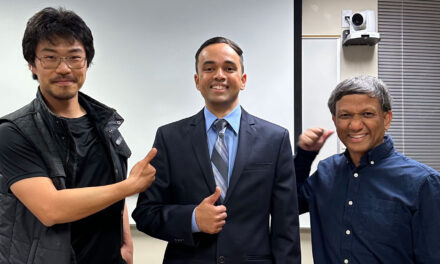

Michael is a professor of computer science and engineering in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University. With a joint appointment in ASU’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society, her research interests converge in the space where biotechnology and cybersecurity meet. Michael’s global collaborations have given her a unique window of insight into how biometric data is collected, stored and utilized.

Each October, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency oversees Cybersecurity Awareness Month to inform the public on ways we can all help make the digital world more secure. For Michael, the proceedings cap a year of efforts that include speaking, writing and collaborating with experts about the growing need to better protect and secure biometric data.

Michael and her colleagues have an important message: We must take action now.

Sensitive data becomes a serious problem

Biometric data refers to information collected about a person’s unique physical attributes. Examples include voice samples, fingerprints and palm prints, facial scans and DNA. This data is useful — and valuable. Some pharmaceutical companies view cheaply-sourced DNA as a way to keep drug development costs down, while hackers seek biometric data to aid in cybercriminal activities.

The data is also irreplaceable.

“Biometric data is us. It’s a part of us,” Michael says. “It’s part of our bodies, and the building blocks of our bodies can’t fundamentally change.”

Michael explains that the trend to collect an increased amount of biological data really kicked off with the rise of facial recognition software.

“There’s a whole ecosystem that has been created around biometrics, particularly since the 1990s, when we had governmental agencies in the U.S. building different types of identity systems,” she says.

In 1993, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency created the Face Recognition Technology program. Created as part of the ongoing U.S. war on drugs, researchers in the initiative developed algorithms that allowed computers to scan and automatically recognize images, building a toolset for law enforcement.

Since then, image collection has become increasingly commonplace and facial recognition tools ubiquitous. Many employers require each employee to be photographed. Experts estimate that 68% of all cell phone users access their devices using facial recognition tools.

Today, it is estimated that approximately 80% of businesses use biometric tools and authentication.

The new biometric bill of rights

Michael has research footprints in the Fulton Schools in Arizona and in the University of Wollongong in Australia, as well as wide connections across the European Union. As the editor-in-chief of the Transactions on Technology and Society, former editor-in-chief of the Technology and Society Magazine and senior editor of Consumer Electronics Magazine all published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, she is well-positioned to understand these critical issues.

She also has a track record for activism in the biometric privacy space. Michael is a past representative to the Consumers’ Federation of Australia and a long-standing board member of the Australian Privacy Foundation.

Michael says the first step in moving the needle on biometric privacy is to engage the broader public in the conversation about this data and its uses. On an individual level, people must stay informed and aware when employers, companies and agencies collect biometrics.

More generally though, she says that an international consensus must be formed to protect sensitive data. Michael believes a new kind of new bill of rights is needed — one that offers key guarantees, like the legal right to have biometric data records destroyed upon request, the right to opt out of the sale or release of personal data and the right to know what information is being collected and stored.

These conversations are starting to happen. Three states and New York City have passed biometric privacy laws, including the Biometric Information Privacy Act in Illinois, which provides many of these types of protections and allows consumers to take legal action when they believe their data has been misused. Citizens in other regions can encourage lawmakers to take similar steps.

But biometric data also suffers from the same cybersecurity concerns as other forms of information. Cybercrime is on the rise, data breaches are increasing, and biometric data is no better protected than usernames, passwords or credit information. In May, the Australia-based photo recognition company Outabox was hacked, while in India thousands of law enforcement officers had their fingerprints and facial scans stolen by cybercriminals.

Michael says that cybersecurity must be thought of in the early stages of a computer system’s design to be effective. She says things are changing — but slowly.

She is also worried about the dangerous increase in deepfakes, highly convincing but false images and videos often made by cybercriminals, that can be generated using compromised biometric data.

“My concern is that with so much uncurbed web scraping happening on the internet, facial biometrics will soon mean nothing as deepfakes proliferate,” she says. “Something truly disastrous might need to happen before action is taken. Sometimes people don’t react until things really hit the fan.”

This Cybersecurity Awareness Month, Michael hopes people will take the time to do something impactful before it’s too late.