Roundabouts: practical yet polarizing

Above: Professor Mike Mamlouk studied the effects of 17 Arizona roundabouts on traffic safety in research funded by the National Transportation Center @ Maryland. Source: Google Earth

Traffic roundabouts are like broccoli. Many of us don’t like them, but they’re good for our driving diets.

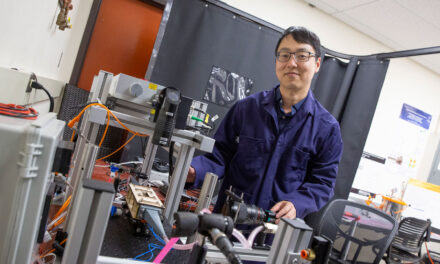

In the right conditions, they increase safety, lower crash severity, reduce traffic delays, and can even reduce greenhouse gas emissions, says Mike Mamlouk, a professor of the civil, environmental and sustainable engineering at Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

Despite their demonstrated safety in other states, they’re a highly polarizing traffic feature in Arizona, which is why Mamlouk decided to study their effects in the Grand Canyon State with former ASU graduate student Beshoy Souliman. Their research was funded by the National Transportation Center @ Maryland, of which ASU is a consortium member.

Since modern roundabouts were first built in the United States in the 1990s they’ve been constructed in most U.S. cities. In Arizona they began popping up more recently, in 2006. Today, the state has around 80 roundabouts, mostly in single-lane and some in double-lane configurations.

Mamlouk and Souliman studied 17 roundabouts in Phoenix, Scottsdale, Sedona, Cottonwood and Prescott to evaluate their effect on crashes and their severity.

They collected data on traffic volume and number and severity of accidents in an equal number of years before and after conversion from a stop sign or traffic signal to a roundabout. Additionally, they looked at crash severity and cost levels from damage only ($11,000 average) to fatality ($1.5 million average).

Modern roundabouts (left) are the newest traffic control system on our roadways, and smaller than older rotaries or traffic circles (right). Source: Melissa Kay Photography, TripAdvisor

Stops vs. roundabouts

Intersections are dangerous places for drivers. Almost half of all traffic collisions in the United States happen at intersections.

Transportation engineers have found that if intersections are designed to be more forgiving — especially for distracted drivers who may run red lights or stop signs — they can minimize accidents or reduce accident severity when drivers make mistakes.

Roundabouts are one solution to this problem. In a roundabout, drivers are required to yield to cars already in the circle before they can merge, and raised lane splitters and medians help reduce traffic speed.

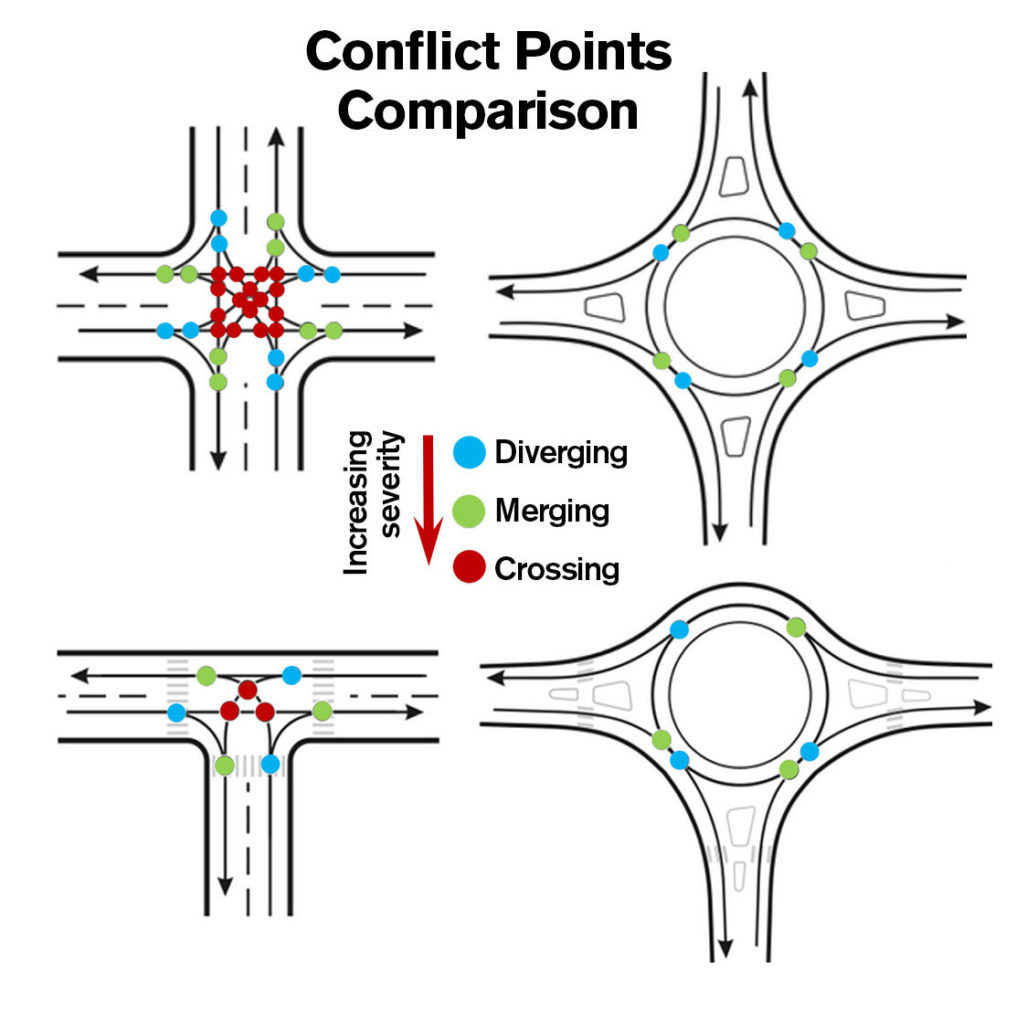

Roundabouts have fewer dangerous conflict points, making accidents less likely to occur and less severe when they do occur. Graphic courtesy of Mike Mamlouk

This configuration eliminates the potential for head-on and right-angle crashes.

“If a motorist runs the red light at a signalized intersection or does not stop at the stop sign, the vehicle will be on the path of crossing vehicles or opposing vehicles when making a left turn, which may result in a major accident,” Mamlouk says. “However, if a motorist enters the roundabout and does not yield to vehicles already in the circle, vehicles will crash at a small angle, causing a low-severity accident.”

Reduced traffic speed as drivers approach the roundabout intersection also reduces crash severity.

He adds that the geometry of a roundabout means there are fewer conflicting points where crashes can occur in roundabouts. So in addition to reducing the severity of crashes, roundabouts reduce the chance of crashes.

Mamlouk and Souliman found that single-lane roundabouts decreased the total accident rate by 18 percent per year, and decreased the injury rate by 44 percent per year.

To Mamlouk’s surprise, two-lane roundabout accidents increased the total accident rate per year by 62 percent. However, these accidents were less severe and the injury rate decreased by 16 percent.

There was one fatality at a single-lane roundabout before conversion and one fatality at a double-lane roundabout before conversion. After roundabout conversions there were no fatalities for both single- and double-lane roundabouts. Also, the average accident cost per intersection decreased for both single- and double-lane roundabouts.

Constructing roundabouts in the right conditions

Though safety improved at the roundabouts the researchers studied, they are effective only in the right conditions, called warrants, which include levels of traffic volume, traffic fluctuation during the day, peak-hour factor, pedestrian volume, school crossing, crash experience and roadway network.

The Federal Highway Administration’s Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices lists warrants for various intersection control types, except roundabouts. Guidelines exist, but the decision is often more subjective than decisions to install stop signs or traffic lights.

“Although no warrants are currently available, engineers use the available guidelines together with previous experience to decide if a roundabout is suitable at an intersection,” Mamlouk says. “Warrants make the decision easier, consistent and more objective.”

When placed correctly, roundabouts also result in non-safety improvements for drivers.

“Instead of stopping at the stop sign or at the red light when no other vehicles are at the intersection, roundabouts allow motorists to proceed with caution without stopping, allowing for free flow movement,” Mamlouk says. “Reducing stopping has the benefit of increasing the intersection capacity and reducing traffic delay and greenhouse gas emission.”

However, when poorly placed, roundabouts can cause increased traffic congestion and crash rates.

Warrants also help determine when a roundabout is no longer needed as traffic conditions change.

Professor Mike Mamlouk

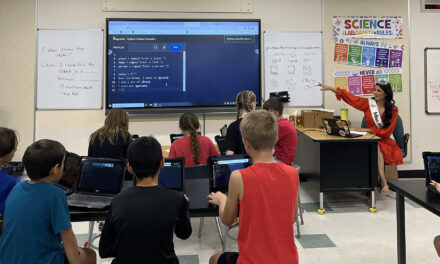

Educating the public

As Mamlouk’s research concludes, he is presenting his findings to public officials to help them carefully assess the specific conditions at intersections before converting them to roundabouts.

As he and other researchers continue to observe and report on roundabout performance, warrants adhering to the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices will begin to be developed.

Mamlouk also hopes to work with public agencies to help educate drivers about the proper use and advantages of roundabouts.

With only 80 roundabout intersections among the thousands of roadway intersections in the state, they’re still fairly rare, and using them correctly can take some practice

“When they introduced the traffic signals in the 1920s, it took people several years to get familiar with the three-color system and understand the rules of the traffic signal,” Mamlouk says. “I am sure people will get familiar with roundabouts with time and experience.”

Just as the basics of using the traffic signal — now a no-brainer to alert drivers — the rules of the roundabout are simple:

“Remember, when getting close to a roundabout, slow down, look left, let vehicles already in the roundabout pass first, and then proceed with caution,” Mamlouk advises.