Calculating a love of math

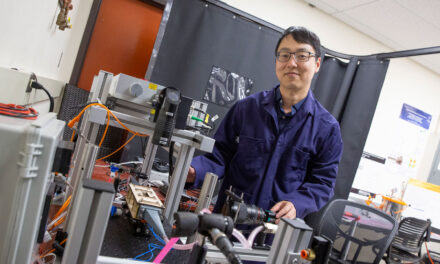

Jim Middleton

Do you like math? We tend to feel strongly one way or another, and likely your decision rides on your experiences in the classroom.

“Mathematics itself is fairly neutral,” says Jim Middleton, a professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering at Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. “There is no reason to either love or hate mathematics outside the experiences we have in and out of school along with the cultural attitudes.”

When students’ enjoyment and understanding of math falters, so do the possibilities of STEM courses and career paths that require higher math in those student’s futures.

To keep math and STEM careers a possibility for all students, Middleton and Amanda Jansen, a professor of mathematics education in the School of Education at the University of Delaware, are studying what contributes to positive student engagement and therefore effective learning.

“These dynamics are not well understood, and as a consequence, mathematics curriculum and instruction in the U.S. is not serving the majority of students well,” Middleton says.

This ASU-UD team is the first to research moment-to-moment experiences of high school students studying mathematics over time as part of their three-year, $1.3 million National Science Foundation-funded study, “Secondary Mathematics, in-the-moment, Longitudinal Engagement Study.”

“We recognized a lack of research that could address, methodologically, how to investigate students’ experiences in the moment to understand the nature of their engagement with mathematics in a way that could reveal more general trends,” Jansen says.

By understanding these processes, they plan to help teachers to encourage more students to engage deeply, work hard, persist and become more mathematically capable.

Engagement = interactions + strategies + tools + organization

“The need for mathematics competencies is so dire, research needs to focus on areas that show the most promise of making positive change in students’ lives,” Middleton says.

Engagement-related variables, such as interest and usefulness, are the strongest predictors of learning, and the most effective place to make a positive change is in the classroom.

“If students are disengaging from mathematics in school, it is likely because school is turning them off from mathematics,” Jansen says.

Figuring out what turns students off of or on to math comes down to the classroom climate. Each classroom has a unique personality based on its students, curricula, strategies for thinking about difficult problems, and cultural attitudes that create a set of constraints on what’s possible for students.

“The big problem is we do not know what teaching strategies and classroom organization patterns impact learners in ways that encourage long-term, positive engagement,” Middleton says.

Middleton and Jansen plan to take into account the different classroom climates and their differences in engagement and mathematical performance to create effective professional development for teachers.

“It is entirely likely that there are many good ways to teach,” Middleton says, “but that some of those ways may be optimally effective in limited contexts.”

Gathering data to learn what best engages students

Amanda Jansen

“Our work has a ‘rubber hits the road’ practicality in that we are focusing on understanding and then changing the learning experiences of students to be more effective, inclusive and personally satisfying,” Middleton says. “This must be done in real classrooms with real teachers and real students so that the dynamics of teaching, learning, feedback and assessment can all be coordinated to contribute to positive outcomes.”

This is the first time secondary math classrooms will be studied so continuously at scale.

“The methodological contribution of this project is an app in which students will be signaled to report what they are currently doing in class and their reactions to this experience,” Jansen says.

Beginning in August, Middleton and Jansen will “mine” real experiences and interactions of more than 5,000 high school freshmen and sophomores in Arizona and Delaware, which together represent the cultural, linguistic and socioeconomic diversity of the United States.

The first two years of high school are a critical time to focus on engagement, Middleton says.

“This two-year period is a tremendous gatekeeper,” Middleton says. “Student struggles are a reflection of the learning experiences they have in the courses they take.”

The rules of math change dramatically from middle school to freshman algebra and again in sophomore geometry. Students often fall behind as they struggle with the content changes from algebra’s rules and computations to geometry’s visualization and proofs.

Middleton and Jansen will look at data collected over two years to see what makes for a successful classroom engagement experience.

“It will be most exciting to find the classrooms where students are more engaged, to understand those classrooms better, so more students have opportunities to learn and love mathematics while in high school,” Jansen says.

The right team to study education

This isn’t the first time Middleton and Jansen have collaborated on studying motivation and engagement in math education.

They’ve each researched mathematics classrooms independently, and together wrote a book for teachers — Motivation Matters and Interest Counts — and conducted an extensive review of the literature on student engagement for an upcoming compendium about mathematics education research with Gerald Goldin, distinguished professor at the Rutgers University School of Education.

Middleton believes he is in the right place to be figuring out how to change math class for the better for all students, educators and the future of STEM professionals.

“ASU is one of the unique places in the world of academia where a school of engineering, as one of its main research themes, focuses on education and education improvement,” Middleton says.

The Fulton Schools in particular take an innovative approach to studying STEM education. Researchers focus on what Middleton calls “education engineering,” in which they look to improve education through the design of teaching and learning tools, technologies, management systems and environments — rather than study “what is” in the field of education, they study “what could be” and how to apply it in real situations.