ASU engineer focused on challenge of renewables for electric grid

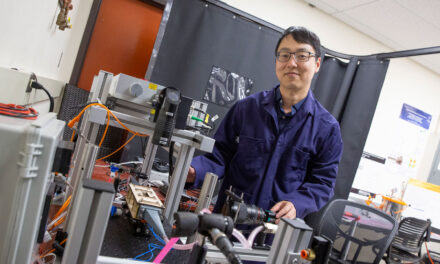

Vijay Vittal

Vijay Vittal’s fascination with electrical engineering began in his home country of India, where he often experienced rolling blackouts.

“The system was primarily hydro-electric, and when the monsoons were good, things worked,” Vittal said. “When the reservoirs were empty, there were blackouts. As a child, I would read the blackout schedules published in the newspaper.”

Today, Vittal is a professor in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, one of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University, and the director of ASU’s Power Systems Engineering Research Center. He also is a Senior Sustainability Scientist at ASU’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability.

His research includes modeling the electrical grid, electrical systems and looking at ways to incorporate sustainable energy, including solar and wind, into the system.

“We’re looking at the electrical grid, how it incorporates renewables, how those devices are intertwined in terms of disturbances, both natural and manmade, and human error,” Vittal said. “New tools are required. Old modeling systems aren’t robust enough to test these things.”

Vittal’s father was a navy officer, and Vittal grew up in Bombay and Delhi. In high school, he took physics, chemistry, math and biology, and originally thought he wanted to be a doctor.

But he first enrolled in engineering classes and, by the time the entrance exam for medical school rolled around, he had decided electrical engineering was his passion.

He earned a bachelor’s degree from the College of Engineering in Bangalore, and a master’s degree from the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur, and moved to the United States to work on his doctorate at Iowa State University in Ames.

Vittal loved the small-town atmosphere and average snowfall of more than 30 inches. After completing his degree, he accepted a position on the faculty and stayed for 23 years, before moving to ASU in 2005.

“By then, my kids were out of the house, and it was the only job I’d ever had,” Vittal said. “I started when I was very young, 24, and I thought if I were ever going to make a move, this was the time.”

Vittal often does post-mortems on electrical failures, like the cascading blackout in 2003.

No one yet knows how the addition of solar and wind power will affect the grid or failures.

“Many states are installing large-scale solar farms,” Vittal said. “Arizona is not as aggressive as California, but regulations require that it have 15 percent renewable sources by 2025.”

Vittal said the inverters required for solar power are faster-acting and so the study of their interaction and effect on the grid requires consideration of the faster time scales.

“We cannot examine them with conventional tools,” he said.

ASU is a leader in the field, with the Quantum Energy and Sustainable Solar Technologies, a National Science Foundation-Department of Energy Engineering Research Center, and the Power Systems Engineering Research Center. QESST is looking at PV materials and PSERC at the technology’s impact on the grid.

“Photovoltaic solar power is pretty expensive for homeowners, including the module, the inverter and storage capacity,” Vittal said. “I think it will be limited to affluent neighborhoods until the costs come down.”

But there are also questions about how solar works on individual homes.

“PV only lasts as long as the sun is out,” Vittal said. “So what do they do at night? They have to have a significantly larger PV module and batteries capable of supplying their needs while they are off the grid at night. Or do they want to be hooked up to the gird, just in case? Some want to be hooked up, but not pay anything unless they draw power. Who, then, pays for the upkeep of the grid?

“What are the requirements for their inverter performance? What happens is there’s an outage? Who do they call to repair it? What is the liability for the crew? How do they know the source of the power flowing through the lines? If there’s an outage, is there a visible disconnect switch so they can work safely?”

In the next five to 10 years, Vittal sees new tools to study and answer these questions.

Vittal said he had a glimpse of teaching while he was still in college and explained some of the difficult concepts to his study group.

“They told me I did a good job,” he said.

He finds teaching very satisfying.

“It recharges my batteries,” he said. “Each student has a different learning curve. I adjust my approach to each of them. I relish the challenge.”

Even though he’s a veteran professor, he still prepares for each lecture, but has never had performance anxiety.

“I’m not afraid to say when I don’t know something,” he said. “I’ll research it and let them know the answer during the next class.”

He’s seen changes in students’ reading habits.

“I think they’re looking at too many screens,” he said. “They have difficulty with textbooks. You need to read and reread to absorb the details. They’re used to skimming.”

But he still finds the students serious.

“These students are very motivated,” he said. “It takes quite a bit of application to study electrical engineering. It’s not just innate ability, but application and staying power.”

Those who persevere will be rewarded, he said, with most graduates having at least two job offers.

“The electrical utilities are in need,” Vittal said. “About 45 percent of the technical staff will retire in the next five years, and you cannot outsource the grid. There will be great demand.

“Arizona Public Service is talking about getting involved with students at an earlier point, as sophomores and juniors, in order to encourage internships and maintain a pipeline.”

In his free time, Vittal volunteers at Andre House, serving breakfast with a group of friends the first Sunday of each month.

He met his wife, Sunanda, in India. She also works at ASU as a technical editor.

He also plays golf, often with his sons. One son, Eknath, 31, is also an electrical engineer with GE, and they frequently discuss electrical issues. His second son, Vinayak, 29, is finishing a doctorate in biochemistry at the University of Washington in Seattle.