Web-delivered education is a huge success as undergraduate electrical engineering program enrollment surges

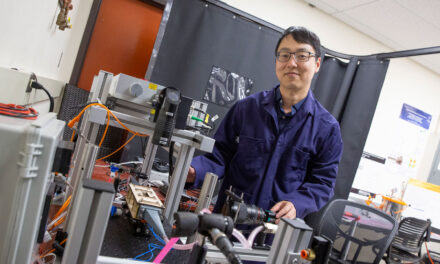

Marco Saraniti, professor, was one of a small group of faculty that started the first four-year, ABET-accredited fully online undergraduate electrical engineering program in the nation.

A small group of faculty began discussions in 2011 about how engineering undergraduate degrees might be offered to remote students. Initially, they surveyed approaches ranging from MOOCs (Massive, Open, Online Courses) to typical online “lecture- capture,” as well as the studio-based online courses being developed at Arizona State University in other disciplines.

The discussions progressed to the launch in 2013 of the first ABET-accredited fully online undergraduate program in electrical engineering in the world. The program serves students — many who are older, raising families, working, or in the military — whose needs have not be met by other academic offerings. Enrollment has surged to more than 800 students in two years and is fast approaching the number of students enrolled in face-to-face classes.

This educational initiative goes well beyond the traditional offering of classes for remote students, and is attempting to define a new educational approach directed to the whole body of students, independent of their geographic location.

In this Q&A, School Director Stephen Phillips (S.P.) and Professor Marco Saraniti (M.S.) director of Web- delivered education in ECEE, discuss the program’s development and success.

Q. How is your program unique?

S.P. We do not segregate online and face-to-face students; we don’t have two programs. We have one program with one accreditation and one body of instructors available in different delivery systems — solely online, in a hybrid online-classroom format, and in a traditional classroom setting. This is the main novelty of our approach.

M.S. Indeed, some of the courses are Web-delivered also to resident students who elect not to go to a physical classroom and to manage their study time autonomously. The only difference is that the resident students take their exams on campus, while the remote students use a proctoring service.

Q. You mentioned the novelty of your approach. What are the main differences from the MOOCs or the online programs offered elsewhere?

M.S. Most of the existing online programs tend

to use modern technology to mimic the effect of traditional lecturing. In other words, they try to adapt new technology to a traditional delivery method. We do exactly the opposite. We design the instructional material around the new technology.

Q. Can you give an example?

S.P. For our introductory circuits course, the students purchase a commercially available lab kit that implements a suite of instruments on their laptops

that is functionally similar to the instruments in our traditional physical lab. It also has a proto-board, where they assemble physical circuits identical to those of the resident students. This approach has been so successful that some of our resident students also want to do the labs at home rather than coming to campus for a scheduled lab session.

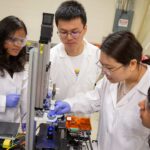

M.S. In another example, Professor Trevor Thornton just received a grant to acquire a remotely controllable electron microscope. I am working with him to prepare an instructional module on electron microscopy. Remote students will first watch videos explaining the theory and practice of electron microscopy. They will then purchase a rather inexpensive kit of chemicals that will allow them to produce samples with suspensions of different nanoparticles.

The samples will be mailed to the lab, where a teaching or lab assistant will physically load the samples in the microscope. The student will then be able to remotely control the microscope, in real time, through a Web interface, and see the images of the nanoparticles they produced. Most of the lab instrumentation today has remote control capability. We can leverage our lab assistants to prepare the lab setup for remote students, as well as the resident students. This approach is completely different than putting a webcam in the back of a laboratory. The whole instructional module is built around the technology, not vice-versa.

Q. How do office hours work?

M.S. For many courses, they are administered using Web-conferencing software for all students, remote and resident. As mentioned, we tend to use the same technology whenever possible. Obviously, resident students can meet their instructors in person, but many prefer the flexibility of Web-conferencing software. And so do the instructors, who are not bound to their offices. We equip our instructors with portable computer tablets so that they can communicate with the students from anywhere, provided they have a Wi-Fi connection.

Q. Isn’t Web conferencing limited? How do you describe a technical diagram, or an equation?

M.S. The instructor shares the screen of the tablet with the student, who can see in real time what the instructor sees and writes on the screen with a stylus. At the end of the session, the handwritten electronic pages are saved in a PDF file that is transferred to the student. During the whole session, both student and instructor can see and talk to each other. This can be more efficient and accessible than meeting in person, and it can be done from anywhere.

Q. How have faculty received the new program?

S.P. I’m happy to report that the program has been received positively by many of our faculty. Our faculty members participating in online instruction have voluntarily performed the relatively lengthy process of developing the instructional material for Web delivery. As we mentioned, this is not a lecture capture, but a separately designed approach to deliver the material via the Web with high production value.

ASU’s EdPlus offers an excellent infrastructure for development, including access to instructional design professionals. EdPlus also provides a financial reward, which is augmented by our school. Most importantly, the quality and the commitment related to course development could not be done without a high level of voluntary participation of the faculty.

M.S. More quantitatively, the development of an individual course can take from 400 to 800 hours of work. This is a significant effort that could not be imposed on our instructors. They do it because they believe in the added value of the program.

Q. Can you elaborate on the “added value” of the program?

M.S. The basic idea of our approach is not to use technology to obtain results similar to those achieved by traditional lecturing. The idea is to use technology to do a better job than with traditional lecturing.

We are trying to achieve two main goals: 1) implement a better process of knowledge transfer, and 2) do it in a more scalable way. In other words, we want to serve more students and we want to do it more effectively than with traditional face-to-face lectures. This approach is not new. The idea of conjugating access and excellence is the intellectual foundation of ASU’s New American University paradigm.

S.P. Another important feature is related to the demographics of our remote students. They are, on average, somewhat older than the resident students, and they are mostly transfer students with some college experience. A high percentage of them are working, and more than a third of them are active military or veterans. So we are serving a segment of the population that has been historically neglected by traditional higher education institutions. You can

see how an appropriate use of technology can be instrumental to providing access to knowledge to a broader audience of students than a traditional delivery.

Q. Did you find any major problems along the way?

M.S. Dozens — this is not an easy task. For example, the educational material needs to be reorganized around the medium and its delivery means. This translates into hundreds of hours of work for each course. This initial investment is arduous, and there’s no alternative to it. We don’t want to put a webcam in the back of a class and produce a subpar product.

At present we have fewer than 20 people in ECEE involved part-time in the project. This includes support staff, the faculty members who develop the material and the ones who deliver the material by actually teaching the classes. The size of this body of educators will increase quickly, and we will have to implement standards for quality control. This is tricky because the novelty of the approach implies the determination of new metrics to assess its effectiveness. However, the new metrics need to be compatible with the ones currently in use for accreditation purposes.

S.P. Another issue is that, while the process of knowledge-transfer is scalable — meaning that we can deliver a course to more students with the same effort — the advising process does not scale. It’s actually less efficient than for the resident students due to the diverse background of these students and the rigorous process for awarding transfer credit. This introduces complexity for our undergraduate advisors and is requiring additional resources.

Q. Why now? Why ASU?

M.S. The traditional approach to higher education is becoming unsustainable. The cost is skyrocketing, while the promise of improving the life of young people through knowledge is less and less certain. A university is a place that does one thing in two steps: generating knowledge and transferring it to students. The traditional approach to this mission is getting progressively less effective and more expensive. This is the reason for the urgency.

S.P. There is a very direct answer to the “Why us?” question. If there is a place where a program like this can be developed effectively, that place is ASU. We have a proud tradition in the introduction of innovative and sometimes unorthodox approaches to higher education. We were the first to prove that it is possible to increase the quality of the services we offer while simultaneously increasing the quantity of people we service. That’s what we are, that’s what we do.