Valuable and vulnerable

ASU engineering experts reframe infrastructure security

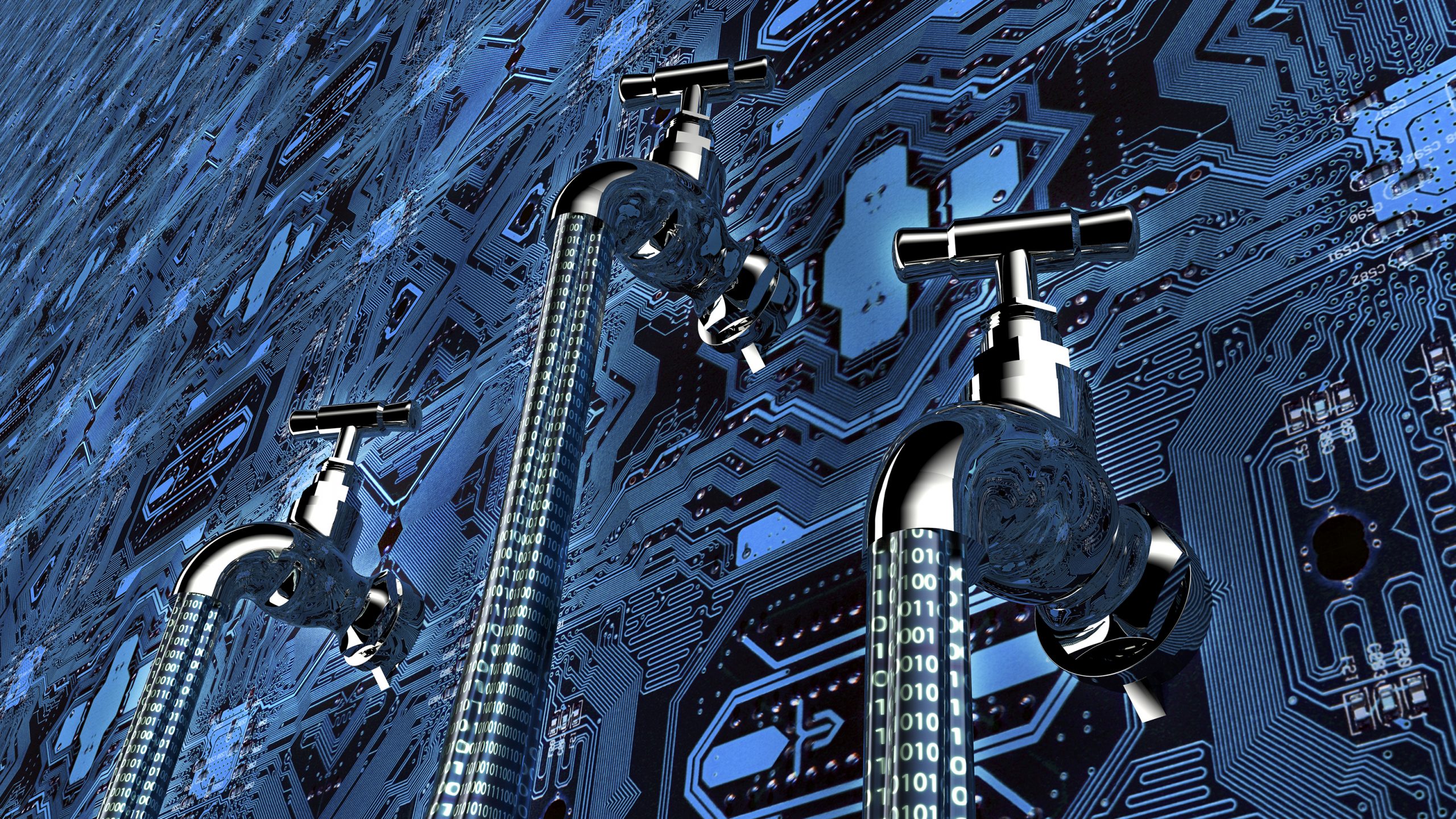

Above: Modern infrastructure systems serve multiple purposes. Pipelines are a means to move liquids, but they also represent networks of sensors and information conduits connected to the wider world. Such advanced functionality demands more advanced security. Graphic courtesy of Shutterstock

“Infrastructure has always been a target in warfare. Think about military aircraft dropping bombs on bridges or railroad lines,” says Mikhail Chester, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Arizona State University. “But battles today are not just army versus army. They are society versus society, and this change means we need to change how we think about infrastructure.”

Chester points to the recent ransomware attack that shut down one of America’s largest fuel pipeline networks. The incident sparked surges in the price of gasoline, panic buying and several days of shortages across the southeastern United States.

“This kind of problem is growing, and it can’t be solved through remedial repairs to old infrastructure,” Chester says. “We need take a step back and ask what a pipeline is in 2021 or in 2100. Yes, it’s a means to move fuel. But it’s also a network of sensors and an information conduit, and that integrated purpose makes it both valuable and vulnerable amid intensifying global competition and conflict.”

Chester and his faculty peers in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at ASU believe broader perspectives need to be part of the current debate about improving America’s infrastructure systems. One issue is the way we frame our thinking about security.

“It’s a multi-domain factor,” says Brad Allenby, a professor of civil, environmental and sustainable engineering in the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, one of the six Fulton Schools. “It’s not a power grid issue, nor a drinking water issue nor an issue for fuel pipelines. It’s a factor everywhere, and that’s the problem. It’s not addressed as it should be because nobody ‘owns’ it.”

Allenby says the time has arrived for the United States to create national cybersecurity requirements for infrastructure development. As part of those requirements, he says any new civil engineering project supported by federal money needs to have a cybersecurity assessment.

Adam Doupé, a Fulton Schools associate professor of computer science and acting director of ASU’s Center for Cybersecurity and Digital Forensics, agrees with Allenby but adds that even a thorough security assessment is only a snapshot in time. Since threats keep evolving, seeking and solving vulnerabilities is not something that can be done once and considered finished.

“We also know as engineers that changing things after a build is more expensive and difficult than it is at the design phase,” Doupé says. “In software, for example, we conduct a security analysis of a system before it’s actually created. And we keep doing that at every stage of development, fixing the problems we find as we go. This software engineering concept could be applied to civil engineering and yield significant benefits as we upgrade our national infrastructure.”

Chester says this kind of cross-disciplinary collaboration is vital to advancing resilience in the power, transportation, water and other systems that enable society to function. But alongside research and development, he says we need to expand our view of engineering education.

“We already do a lot to enable emerging and disruptive technologies that expand the functionality and improve the efficiency of our civil systems,” he says. “But successfully managing the transitions we face as a society includes thinking about how we see a civil engineer today versus what we envision a civil engineer as needing to be in the years ahead.”

Chester and Allenby say that engineering’s core competencies now need to include cybersecurity. Doupé notes that the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, or ABET, requires that all university computer science students be exposed to security concepts.

“And at ASU, we’ve been very proactive in requiring that all computer science students take our introduction to cybersecurity course. But we can broaden that requirement,” Doupé says.

“Yes,” says Allenby. “We can make security a mandatory part of all engineering degrees. Engineers need to understand the security implications of what they do. But education is not just about universities. Professional associations have a role to play in training. There are many ways in which we can stay on top of security.”

Doupé adds that equipping engineers to stay on top of security is vital to avoiding more ransomware attacks of the kind that struck the fuel pipeline network in the southeastern U.S. — or worse.

“If that situation caused as much disruption as it did,” he says, “imagine what would happen if an entire city’s power grid gets seized for ransom.”

Basic hygiene

Engineers build bridges to carry remarkable loads and withstand powerful winds. But the challenges of infrastructure security are not just physical forces or Mother Nature.

The dangers include human adversaries who learn how a system works and then plan to make trouble. And while there are cybercriminals capable of defeating almost any security measures, a great deal of protection can be achieved through what Adam Doupé calls basic hygiene.

“When a computer requests user permission to conduct an important security update, most people click ‘remind me later’,” says Doupé, an associate professor of computer science in the School of Computing, Informatics, and Decision Systems Engineering, one of the six Fulton Schools at ASU. “However, if it’s one of the computers running a power grid, it’s probably vital to make sure those updates are in place.”

But Doupé says even these simple measures can be difficult to implement for a variety of valid reasons. One example may be when computers supporting a utility system have been certified for one particular use case.

“The company running that system could be very hesitant to apply updates out of fear that it will cause operational problems,” Doupé says. “That’s one of the key challenges of computer security right now. We tend to push the task of testing onto end users. So, we need to think about how to offer these security patches with assurance that they are not going to compromise functionality. It’s not necessarily a complex issue, but we need to address it.”